Deglobalisation is the idea that the integration of the world economy is going into reverse. But is it actually happening? After decades of globalisation, will the future be one of economic conflict between rival trade blocs?

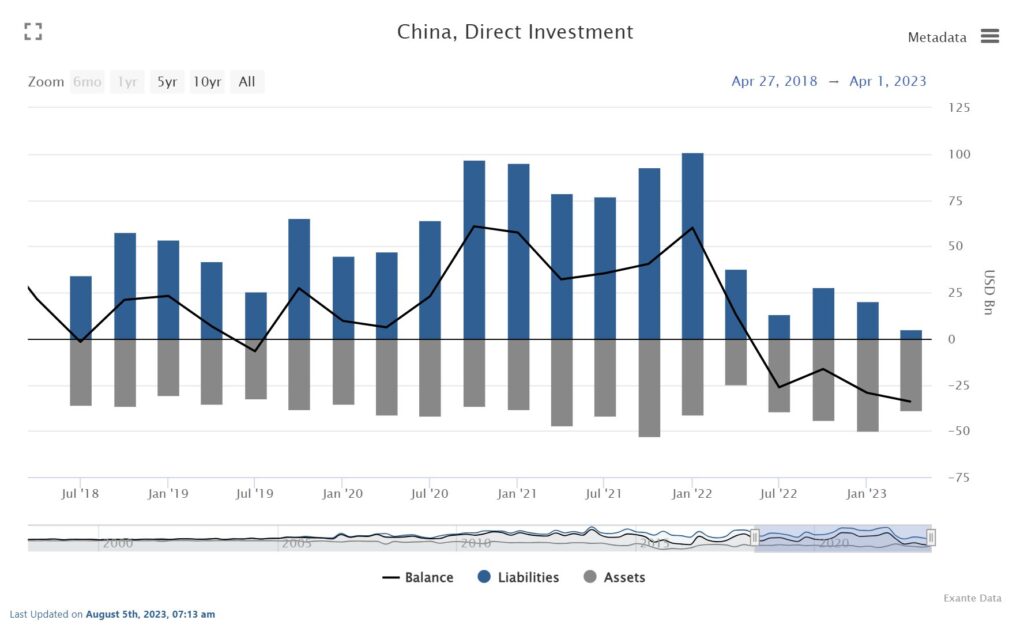

The following chart appears to provide an omen. Shared on Twitter this weekend by the investor Jens Nordvig, it shows a steep decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) in China.

Nordvig adds that in the second quarter of 2023 foreign investors “only put about $5bn of fresh capital into China […] in 2021, we saw close to $100bn per quarter!”

There are many forms of foreign investment, but one of the most important is (or perhaps was) the wholesale offshoring of the West’s industrial capacity. This mega-trend has changed all of our lives by flooding consumer markets with cheap goods, while degrading the productive side of our economies — and in particular the availability of well-paid jobs in manufacturing.

If this process is now coming to an end — or at least slowing to a crawl — then that’s a big deal.

Of course, it’s tempting to dismiss this development as yet another Covid side-effect. The disruption of supply chains has played all kinds of havoc with the global economy. Until normal service is slowly and painfully restored, it wouldn’t be surprising if Western investors in China were holding back temporarily.

Except that Covid hasn’t just exposed the vulnerability of a globalised economy to pandemics, but also something more enduring, which is the true nature of the Chinese state. From the cover-up of the origin of the virus to the draconian imposition (and sudden collapse) of China’s Zero Covid policy, the depredations — and limitations — of Xi Jinping’s dystopian rule are plain for all to see.

Then there’s the Ukraine effect. China is not the only non-Western power to maintain close relations with Russia. However, unlike India or Brazil, China has also continued to threaten war against a state with close ties to the West — in this case Taiwan. The experience of companies like McDonald’s in Russia provides an example of what would happen to Western investments in China if President Xi went full Putin and ordered an invasion of his own. Even if peace is more likely to be maintained than not in the South China Sea, why would Western investors run such a risk?

There’s also the vulnerability of China’s export-oriented economy at a time when the West is waking up to the danger of depending on dictatorial regimes. For instance, Italy has announced its intention to leave the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — which is China’s multi-trillion-dollar programme to build (and control) a Eurasian trade network. The Italian Defence Minister described his country’s previous decision to join the BRI as “atrocious” and voiced concerns about the Chinese government’s “increasingly assertive attitudes”.

There has always been a self-hating tendency at work in the West. Guilt-stricken liberals, subversive Leftists and Putin-loving populists delight in the rise of the non-Western powers and the various humiliations of the free world. But while there’s nothing wrong with learning our limits, we shouldn’t imagine that countries like China are invincible, or that they won’t suffer the consequences of their own arrogance.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe Chinese economy has always been shaky. Real estate speculation bolstered by untrammeled provincial borrowing and lending. Look at the disastrous decline of some Chinese real estate moguls. Sudden major ideological impositions on private enterprise. What happened to Baidu? Hesitation to invest in China is perfectly reasonable and prudent, and does not require wider deglobalization beliefs.

The Chinese economy has always been shaky. Real estate speculation bolstered by untrammeled provincial borrowing and lending. Look at the disastrous decline of some Chinese real estate moguls. Sudden major ideological impositions on private enterprise. What happened to Baidu? Hesitation to invest in China is perfectly reasonable and prudent, and does not require wider deglobalization beliefs.

“There are many forms of foreign investment, but one of the most important is (or perhaps was) the wholesale offshoring of the West’s industrial capacity. This mega-trend has changed all of our lives by flooding consumer markets with cheap goods, while degrading the productive side of our economies — and in particular the availability of well-paid jobs in manufacturing.

If this process is now coming to an end — or at least slowing to a crawl — then that’s a big deal.”

Maybe it is coming to an end because we have very little left to offshore except welfare and illegal immigrants

“There are many forms of foreign investment, but one of the most important is (or perhaps was) the wholesale offshoring of the West’s industrial capacity. This mega-trend has changed all of our lives by flooding consumer markets with cheap goods, while degrading the productive side of our economies — and in particular the availability of well-paid jobs in manufacturing.

If this process is now coming to an end — or at least slowing to a crawl — then that’s a big deal.”

Maybe it is coming to an end because we have very little left to offshore except welfare and illegal immigrants

Deglobalising. Sounds wonderful! The world has finally realized globalization is the biggest scam in history by greedy finance, tech, and corporations in concert with politicians and bureaucrats. The low cost goods, read cheap, came at a steep price for the working folks of the world. Who would really sell out their country and communities for more money and power? Well, the list is long and if the real truth is that the Bidens were nothing but grifters, it will be time to play some real catch-up on the perpetrators. About time!

Deglobalising. Sounds wonderful! The world has finally realized globalization is the biggest scam in history by greedy finance, tech, and corporations in concert with politicians and bureaucrats. The low cost goods, read cheap, came at a steep price for the working folks of the world. Who would really sell out their country and communities for more money and power? Well, the list is long and if the real truth is that the Bidens were nothing but grifters, it will be time to play some real catch-up on the perpetrators. About time!

Short, informative article. I appreciate the info.

But what’s this about? “Guilt-stricken liberals, subversive Leftists and Putin-loving populists delight in the rise of the non-Western powers and the various humiliations of the free world.”

I thought it was fairly self explanatory, in that there’s always been groups that like to talk up other countries while denigrating their own. Russia has always been a favourite target of these people, first by the hard left praising its communist regime (while ignoring the struggles of its population) during the days of the Soviet Union, and more recently by the online right who portray Putin as a strong leader standing up for masculinity. The fact none of these groups ever moved there, choosing instead to live in the freedom of the evil decadent West does expose the hypocrisy of their arguments

Truly, as someone who has traveled a lot, it pains me whenever I hear Americans who’ve never left their country painting it as the center of oppressive evil.

As much as I like Americans, many of them really do see themselves engaging in a struggle between good and evil.

Truly, as someone who has traveled a lot, it pains me whenever I hear Americans who’ve never left their country painting it as the center of oppressive evil.

As much as I like Americans, many of them really do see themselves engaging in a struggle between good and evil.

I thought it was fairly self explanatory, in that there’s always been groups that like to talk up other countries while denigrating their own. Russia has always been a favourite target of these people, first by the hard left praising its communist regime (while ignoring the struggles of its population) during the days of the Soviet Union, and more recently by the online right who portray Putin as a strong leader standing up for masculinity. The fact none of these groups ever moved there, choosing instead to live in the freedom of the evil decadent West does expose the hypocrisy of their arguments

Short, informative article. I appreciate the info.

But what’s this about? “Guilt-stricken liberals, subversive Leftists and Putin-loving populists delight in the rise of the non-Western powers and the various humiliations of the free world.”

Where are all the comments?

Has Branagan ‘flagged’ them all as usual?

Where are all the comments?

Has Branagan ‘flagged’ them all as usual?

China is discovering that a centrally planned economy with many enterprises being state controlled is not a good formula for growth thus outside investment falling. While economic control allowed considerable investment in their military that too has become a warning for outside investors. Their export economy has produced a excess of wealth but at the expense of other nations where capital is less at risk and returns might be more secure. China is seeing a decline and has started some policy reversals but until their military reduces those policy changes may not be enough.

China is discovering that a centrally planned economy with many enterprises being state controlled is not a good formula for growth thus outside investment falling. While economic control allowed considerable investment in their military that too has become a warning for outside investors. Their export economy has produced a excess of wealth but at the expense of other nations where capital is less at risk and returns might be more secure. China is seeing a decline and has started some policy reversals but until their military reduces those policy changes may not be enough.

India is increasingly hoovering up purchases made via Amazon. Sport’s gear made in India or China – you choose.

“ However, unlike India or Brazil, China has also continued to threaten war against a state with close ties to the West — in this case Taiwan.”

No more than when China was a favourite of the west. China has always claimed Taiwan, and vice versa

At the risk of getting downvoted for facts, Taiwan isn’t in fact an ally of the west. It’s not even recognised as a sovereign country by most. It exchanges no ambassadors with any western country. Both Taiwan and China claim jurisdiction over each other, and since the 70s the world has recognised the PRC. Only 13 largely tiny countries recognise Taiwan and the U.K. isn’t one of them.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan–United_Kingdom_relations

Also

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-taiwan

As for the decline in china’s growth it’s above target as far as I can see.

You may be getting downvoted for facts that are non sequiturs. “Close ties” means trade, which in the case of Taiwan is critical trade in electronics – the fact that the US Formally recognizes the PRC and not Taiwan is insignificant, especially considering we might be in a shooting war defending that island in the near future.

No. Close ties means economic and primarily political ties.

I bet most Americans couldn’t find Taiwan on a map, and a large minority would have trouble finding China on a map. Unherd is hilarious – anti the MSM unless the MSM is pushing another neo conservative war against a country far far away. Hat tip – if the US wants to dominate a new American century then it needs far more immigration than it has already. You can have your conservatism or your imperialism – you can’t have both.

No. Close ties means economic and primarily political ties.

I bet most Americans couldn’t find Taiwan on a map, and a large minority would have trouble finding China on a map. Unherd is hilarious – anti the MSM unless the MSM is pushing another neo conservative war against a country far far away. Hat tip – if the US wants to dominate a new American century then it needs far more immigration than it has already. You can have your conservatism or your imperialism – you can’t have both.

You may be getting downvoted for facts that are non sequiturs. “Close ties” means trade, which in the case of Taiwan is critical trade in electronics – the fact that the US Formally recognizes the PRC and not Taiwan is insignificant, especially considering we might be in a shooting war defending that island in the near future.

“ However, unlike India or Brazil, China has also continued to threaten war against a state with close ties to the West — in this case Taiwan.”

No more than when China was a favourite of the west. China has always claimed Taiwan, and vice versa

At the risk of getting downvoted for facts, Taiwan isn’t in fact an ally of the west. It’s not even recognised as a sovereign country by most. It exchanges no ambassadors with any western country. Both Taiwan and China claim jurisdiction over each other, and since the 70s the world has recognised the PRC. Only 13 largely tiny countries recognise Taiwan and the U.K. isn’t one of them.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiwan–United_Kingdom_relations

Also

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-taiwan

As for the decline in china’s growth it’s above target as far as I can see.

The World is clearly dividing into East and West Blocs. The reason is also clear: Mr Biden is an aggressive President, relying on military and economic force rather than negotiation. It’s not the best arrangement, but it’s ok: the world is large enough to hold two rival, separate, antagonistic Blocs. Its the Cold War, again, written larger. That’s the world Mr Biden knows and prefers.

The World is clearly dividing into East and West Blocs. The reason is also clear: Mr Biden is an aggressive President, relying on military and economic force rather than negotiation. It’s not the best arrangement, but it’s ok: the world is large enough to hold two rival, separate, antagonistic Blocs. Its the Cold War, again, written larger. That’s the world Mr Biden knows and prefers.

This article is so bad, so full of racist hate baiting, it doesn’t deserve a comment!

Seems like reasonable observations to me and quite gratifying to see China get what they deserve.

Say what? Where is the hate baiting? Calling China dictatorial?

Yet you couldn’t help yourself commenting could you Branagan you rather transparent Chinese stooge?

Perhaps you are denying you are racist – even to yourself – so that whenever anything relating to race comes up, your subconscious is aroused and you have to outwardly deny what makes you uncomfortable about yourself.

Racist, schmecist, and Hate, schmate.

…and yet, here you are…

Why post one then….?

Seems like reasonable observations to me and quite gratifying to see China get what they deserve.

Say what? Where is the hate baiting? Calling China dictatorial?

Yet you couldn’t help yourself commenting could you Branagan you rather transparent Chinese stooge?

Perhaps you are denying you are racist – even to yourself – so that whenever anything relating to race comes up, your subconscious is aroused and you have to outwardly deny what makes you uncomfortable about yourself.

Racist, schmecist, and Hate, schmate.

…and yet, here you are…

Why post one then….?

This article is so bad, so full of racist hate baiting, it doesn’t deserve a comment!