Sections of the media seem unable to report on any Covid-19-related news without finding within it a sure sign of impending disaster. I suppose it’s a conception of ‘responsible reporting’ (don’t tell people anything that might make them cavalier about the threat), or perhaps it’s just that bad news sells, but it is starting to feel like a parallel universe.

Take the curious phenomenon of the average age of new Covid-19 infections coming down, dramatically, across the world. This is really not bad news: obviously it would be better if no-one was getting infected, but if people are getting infected it is surely better to have younger people infected than older people, for the simple reason that they are far, far less likely to die of it. We should want the average age of new infections to be as low as possible.

You wouldn’t guess it from the coverage.

“As virus surges, young people account for ‘disturbing’ number of cases,” screamed The New York Times last week, revealing that more than half of new cases in Arizona and parts of Texas are under 44, and that the median age of new cases in Florida has plummeted from 65 in March to 35 more recently. “The dropping age of the infected is becoming one of the most pressing problems for local officials” reported Bloomberg, ominously. Not as ‘pressing’ as it would be if the average age of the infected was increasing, presumably — because then there’d be many more people getting sick and dying.

States like Florida and Arizona are seeing a genuine surge, so it is understandable that people are concerned, and it is translating into an uptick in hospitalisations and deaths. But the fact that most of these cases are among younger people is a mercy, as it should mean that these infections will translate to fewer hospitalisations and deaths than the equivalent number of cases among older people.

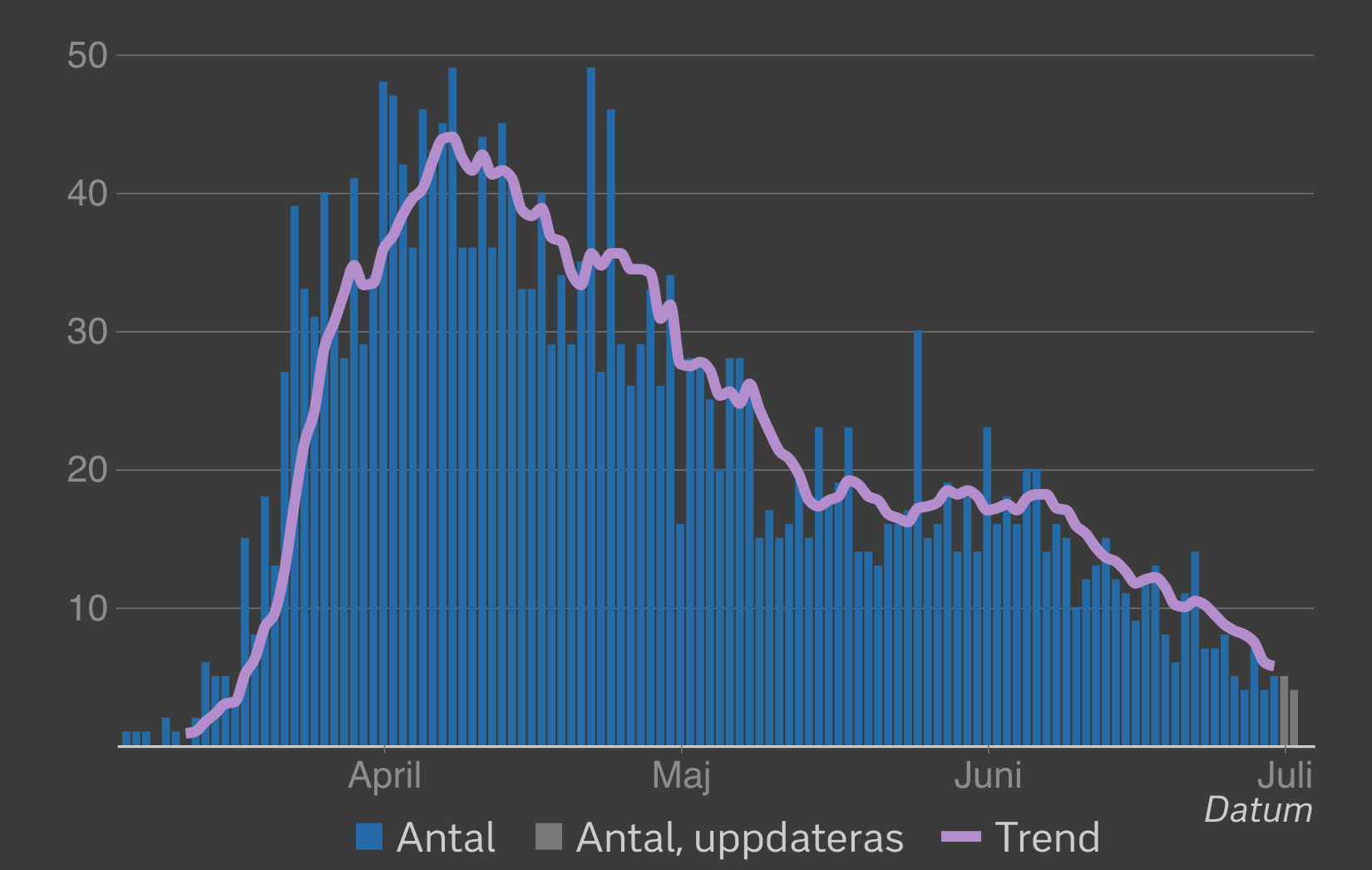

Sweden suffers a continual drumbeat of horror stories and horror charts showing surges in case numbers, but the state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell insists that it’s entirely a function of increased testing. Once again, the age profile of these new cases is younger and younger. Every day I check the chart for new admissions into intensive care in Sweden, awaiting the real-world effects of all these new cases, but every day the trend line continues downwards. As of today there are 127 people in ICU with Covid-19 in Sweden, a country of 10 million people.

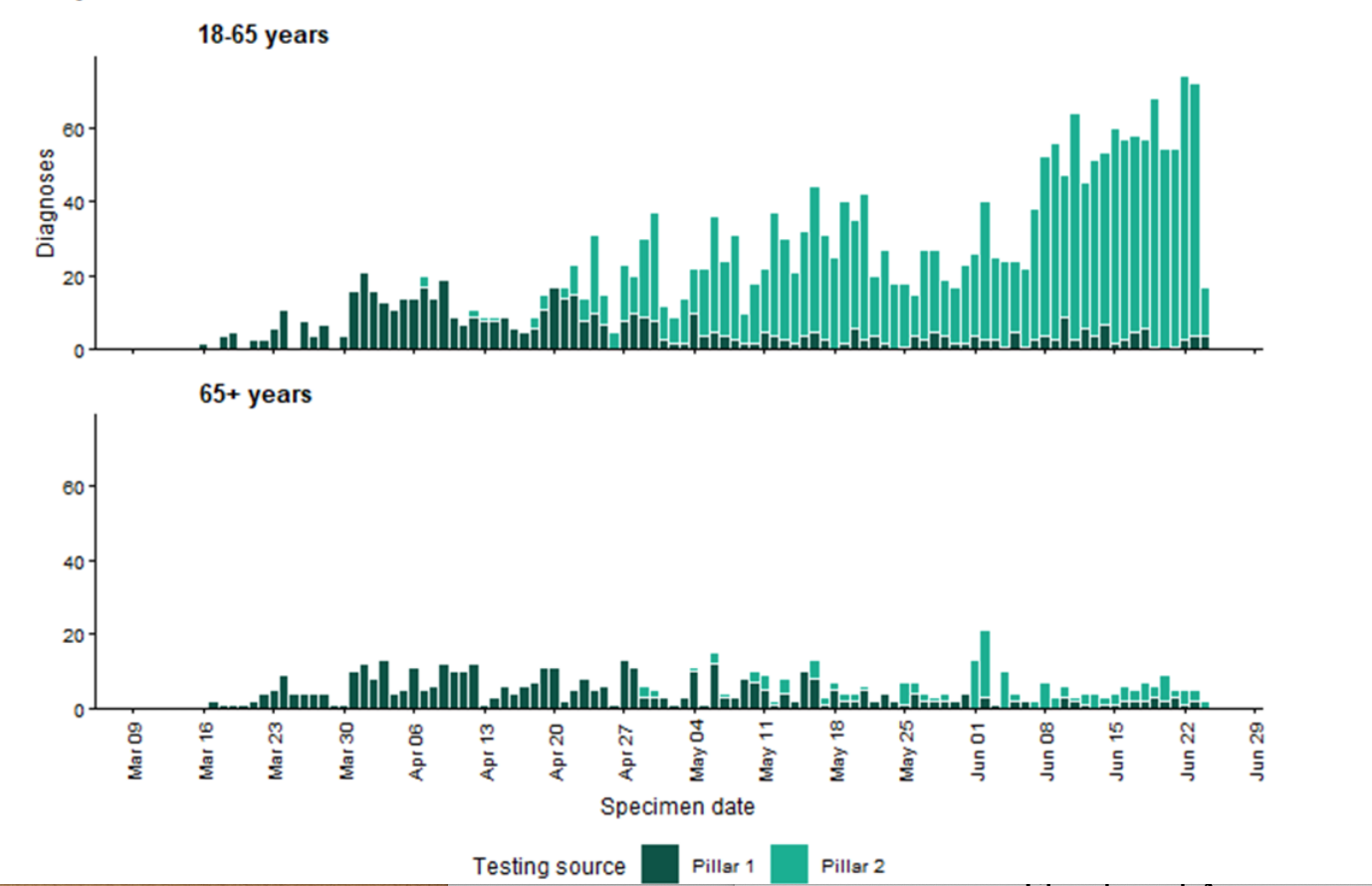

Closer to home, hidden in the very detailed report by Public Health England into the Leicester outbreak that has led to an extended lockdown in that city, is the same detail:

As with elsewhere, this is partly increased testing identifying a greater number of hidden cases (the report’s authors acknowledge that they can’t be sure there’s been any surge at all), but it could also be to do with protests, relaxing lockdown rules, or many other things. Whatever the reason, it should mean that the frightening surge of case numbers in Leicester, as in Florida and Arizona, won’t translate to a commensurate surge in hospitalisations and deaths. I’d put that on the ‘positive news’ ledger —but it is not reported that way.

Infections in Leicester

The counter-argument, of course, is that increasing numbers of young people getting sick will translate into increasing numbers of old people getting sick in time, as they go to see their grandparents etc. Well, let’s see. The Leicester ‘surge’ has already happened and it has not been observed elsewhere to the same degree. So we have something like a controlled experiment.

So far, there is no clear effect on Leicester hospitals, which report that they are not under pressure and are not seeing an increase in deaths. We need to keep an eye on the size of the effect for the next few weeks — if there is only a very small effect, please don’t let anyone get away with saying it is a ‘success of the local lockdown.’ We’ve seen the charts: the surge already happened prior to any new action. The data coming out of Leicester in the next few weeks should tell us a lot about the real-world effects of these apparent case surges of mainly young people, and how worried about them we should really be.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeIt could be that in a lot of countries (especially Europe) COVID 19 has already killed a large percentage of the people it was going to kill and that declining death rates are due to a lack of susceptible people. The data from numerous countries, using varying mitigation strategies is now starting to look very broadly the same, except for some islands such as Japan Taiwan and Australia etc. This nasty virus undoubtedly kills the old and the sick/vulnerable. We should not be surprised if/when people outside those categories should begin to view it as no great risk to their health. That’s the main problem with most government’s ” it’s going to kill us all ” style messaging. The data doesn’t back it up…well not if you are under 40 and in good health anyway.

So far I only noticed Johan Giesecke, early on, mentioning “thinning of the herd”. But this seems an obvious consideration which points more optimisticly toward the remainder of the pandemic.

Very importantly, IMO, buttressing a likelihood that this type of effect could be very much underestimated, is the growing number of studies indicating that so-called “seroprevalence” (a dumb medical term, as are many) is a poor indicator of exposure and of adaptive immune status for SARS-CoV-2.

I have seen informed estimates of only 20% of those with adaptive immune status showing IgG antibodies. That should be very unsurprising to anyone familiar with coronaviruses in general.

Japan, Taiwan, Australia (and to a large extent, most parts of mainland China) will be wrestling with this virus indefinitely unless they change their approach to allow contagion more liberally. That is, unless a vaccine is very successful, and the same knowledge of CoVs’ lack of humoral stimulation/response should make one skeptical of the likelihood of good success with vaccination despite the huge R&D effort being applied. Similarly, the time to develop a very successful vaccine solution is more likely to be long.

The fact that so many efforts appear to be focusing almost solely upon epitopic antigen features bodes poorly for likelihood of success IMO. Same goes for the introduction of so many novel (and hence untested in general) methodologies.

A cocktail of vaccines might have a better chance of success. What about cognate-antigen targeting vaccines for instance? All of this is very speculative though, at best.

The role of the cell-mediated immune response seems to be grossly unrecognized in the medical and pharmaceutical fields, and of course in the media and public at large too.

Indeed, without active cell-mediated response to a virus or to a vaccine, antibodies cannot be effective. This much is well known to the field of immunology. How much of the detail of the underlying mechanisms are understood I am not sure, but I would guess not much at all. Historically, virus vaccines seem to target primarily epitopic features/antigens but nevertheless depend for their success largely upon successful stimulation of the cell-mediated response. This suggests to me that there is would be a rapidly decreasing chance of success the more “artificial” the vaccine antigen presentation is. In other words, the less fully molecularly similar the vaccine is to the real virus, the less chance of success.

I would bet much more heavily upon the older, more experienced players in the vaccine development field. It is more than apparent to me that many who have jumped in without background (e.g. Moderna) are highly ignorant. And unsurprisingly, the older players are more cautious in their public statements.

Oh, thank you so much for this! As a resident of NYC, I have been frustrated and alienated by the coverage in the NY Times almost from the beginning of the pandemic, and have wished for more opinions and analyses from Ionnadis, Katz, Gupta, Sikora, Wittkowski, et al. to offer (at least) a different perspective. The misinformation and unscientific articles continue, and continue to spook the populace and local government. As we have been saying and saying, we have to wait and see – it would be terrible if the infection rate among young people causes as many deaths as it had among the more vulnerable – but so far, what we know about COVID19 argues against that possibility. So, my family and I appreciate your voice.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend tuning into watch the 2 hour weekly health freedom show, thehighwire.com with Del Bigtree, founder of the Informed Consent Action Network, icandecide.org. He has been ahead of the story from the get go, and frequently interviews scientists, medical doctors, activists, politicians, legal experts, etc. with a range of perspectives, most challenging the MSM narrative on this and other health related issues:))

Freddy, your interviews and magazine, in general, have been a lifeline during this nightmare, and I am forever grateful for the sanity it has provided. Keep up the great work, please. Also, regarding this particular post, more focus on the adverse effects of lockdown and the new normal health protocols upon young people (schools and universities), would be GREATLY appreciated.

In the US these are trending from the ridiculous to the absurd, given what is known now about the minimal effects of covid-19 on the young, and their low incidence of transmission to adults.

What I am witnessing around me here on the west coast is nothing less than catastrophic PSTD among young people, affecting their studies and wellbeing dramatically. It is beyond sad; for example, my 17 year old daughter is being advised that should her pre-professional ballet training continue in person in the Fall, students will be required to take multiple daily classes in masks!!! The hodge podge of requirements and regulations from these institutions display, at best, dismal public health “science” and possibly, at worst, child abuse. One neighbor, quit teaching in a montessori pre-school this week after 15 years as head teacher, and recently being asked to oversee 3 year olds required to wear masks, I kid you not. You just can’t make this stuff up! Show me the science that all these rigid protocols actually make ANYONE safer. Surely the best outcome would be for the kids to go through the usual first two weeks of school with likely minor sniffles, if anything, and then be done with it.

I apologize if this is a bit off topic, but the short and longer term adverse effects of these government and institutional policies upon young people truly is criminal: as ever, the extraordinary popular delusions and madness of crowds!!!

They are not absurd. Covid is not always mild in children. It has caused a Kawasaki’s like syndrome in a number of children, involving serious, even fatal, heart disease. And I have read accounts of many children and young people dying of Covid. Most recover (maybe), but a large number have died.

Wearing a mask keeps your germs on the inside and other people’s germs on the outside. Schools would be irresponsible if they didn’t try to keep it that way.

In Italy, as elsewhere, in many cases grandparents caught Covid from their grandchildren and died of it. There is nothing absurd about trying to protect vulnerable people from a disease so often so rough on them.

As a vulnerable person I am happy to protect myself, thank you very much. I am glad that the young who want to take chances are doing so and getting us that much closer to herd immunity, which is our ONLY salvation.

I’ve been telling anyone who will listen that cases going up, without a rise in deaths, is fantastic news. Young and old, vulnerable and not, are doing what’s best. The young are doing their civic duty, getting exposed, gaining immunity. Older folks are fully aware by now of their risk, and are being cautious. I fear renewed lockdown, because it only delays the inevitable at huge cost.

Delay is worth everything. Most viruses mutate to become milder over time, and Covid seems to be no exception. And over time people get subclinical exposure to a virus so prevalent in the environment and their immune systems develop both specific and non-specific defenses that prepare them to cope successfully with the virus. Better treatment protocols are developed over time. Buying time is a good strategy and I think we’ll just have to see how it goes and how the situation evolves.

Not at the expense of the tens of millions of people out of work and the tens of thousands who had other medical procedures – some critical – delayed. Sorry. Suck it up.

So much real brutality and discrimination in the modern World to cry out about and try to change, but Western elites and intelligentsia (unintelligentia, might better describe them these days) babble about past healed wounds, and centuries old resolved issues, non-problems, so as to signal their virtue cost-free without having actually to do anything of consequence and get their hands dirty.

Another good article from Freddie.

He says “..127 people in ICU with Covid-19 in Sweden..”.

Yesterday there were 276 in the whole of UK:

https://www.cebm.net/covid-…

UK population is more than 6 times that of Sweden!

Great article. Folks hate it when Trump is (sort of) right, but his comments about more testing=more cases was actually insightful. Big-name epidemiologists have made the same point. As testing comes online our denominator gets bigger and bigger. This can happen even as deaths flatline or fall.

When I first heard trump say his slogan, I was how stupid. But it is actually quite true, although I think he made this comment out of stupidity. The test has been developed so quickly, it shows up quite a few false negatives. And corona is a common virus, which could have been in bodies for years. They have now found out it was present in Barcelona in 2013? or 2016? The same with testing all the meat factory workers, corona comes from animals, the worker could have the virus from the animal in their system. Most people do not have any symptoms, so why is it soo important to know if they are infected? Just to push up the numbers and scare people?

The quality of editing leaves a lot to be desired. When referring to a key source in the article, the very well known pundit Mickey Kaus, the author goes with Kraus once but settles on Klaus as his wrong reference every other time. And says George W. Bush, not his father George Bush, beat Dukakis. That sloppiness doesn’t add to the credibility of such a speculative piece.

I have heard the prevalent argument still recently that we have to continue to keep the entire population locked down in order to reduce the chance of infection of the elderly by the younger.

This is so upside-down and asinine as to begger belief, especially at this stage now that a lot is known about the virus.

There are simple and obvious methods to protect the elderly, as well as their own voluntary choices to do so based upon their own tradeoffs. But extensive regular testing of those working within nursing/care homes, careful management and reduction of traffic in and out of these facilities, and so forth are straightforward and can be encouraged, assisted and enforced by governments.

Upgrading of ventilation systems is a much longer-term project but should be embarked upon by now.

All of these policies would be trivial in cost compared to that of universal lockdowns of the population.

Clearly it is best for the more robust to get on, without any unnecessary delay, of developing endogenous immunity to this virus.

It is going to be very interesting to see if a second (cold/flu) season is substantial in various countries and localalities. I suspect that the low estimates of exposure by antibody studies are exactly that — low. CoV-2 spreads less rapidly than flu for sure, but not all that slowly. I am very skeptical that the seroprevalence studies are not highly misleading, because they are testing for a poor biomarker wrt CoV-2.

Sweden and the US are the countries to watch — these countries will be first to achieve substantial and then robust herd immunity. More specifically, one should watch those local regions earlier and more heavily affected. I see all sorts of signs that these regions are already substantially immune to the virus, with no surprises indicating otherwise so far. It is unfortunate that most or all of these regions (in USA) are stubbornly resistant to quickly and completely opening back up.

Kenneth, thanks for your informative posts. I learn a lot from them.

Meanwhile, while the pharmaceutical industry will continue to quietly fight this with “tooth and nail”, and they have been very successful in doing so for a long time now, individuals should wise up and look after their vit D status. This alone, at population-wide level, would probably almost eliminate both flu and CoV and other respiratory endemic viral infections.

How one can compare the sterilisation of a mentally defective woman who reproduces and passes the responsibility and cost of caring for her children on to taxpayers (they have human rights too, you know) with the systematic destruction of a people and culture is, well, quite beyond me. The writer needs to get some perspective.

Having worked with quite able, and less able, people with learning disabilities, to be coarse, who’s f*****g DD? If it’s not another person with a learning disability the question is why were they not prosecuted, statutory rape is the usual charge. Those I worked with usually had contraceptive implants, and were often at it like rabbits, as they lacked the usual social/sexual inhibitions. As for the Chinese and the Uighurs and the misuse of the health system, perhaps the WHO should investigate?

I think the wrier was trying to give that perspective by pointing out the difference between a “last resort” ruling born of deep reasoning in a particular case, and the abhorrent eugenics reasoning of other forced sterilisations (such as the Uighurs) .

Freddie, I check the Swedish data less regularly than you, but with the same findings.

More often I check the data for my own state of Massachusetts in USA. It is has one of the highest per-capital accruals in the USA for deaths so far.

The state gov’t has been horribly incompetent in every respect, and the large number of deaths in nursing (i.e. care) homes reflects their irresponsibility and incompetence and corruption (nursing homes have been heavy contributors to all of the powerful politicians).

But it may likely be that the lockdown of Mass. lagged that of neighboring NY (for example) more than the spread of the virus in each region respectively.

If so, this would have given Mass. a better/longer uninterrupted head start toward herd immunity. Mass. just had a day with zero reported new deaths for the first time since the beginning, and all of the relevant data indicates an inexorable continuing decline of deaths and hospitalizations and so forth. These data are generally on the order of one fifth that of the early/peak weeks now, and still not clearly leveling off.

There is only one possible cause of this — natural endogenous immunity. In Milan MDs notice a huge reduction in typical viral load in recent infections. This is, I think, a likely large epidemiological feedback factor but still underappreciated, and one that will tend to allow for continued spread of the virus with ongoing buildup of immunity but with much more attenuated prevalence of serious complications.

The mainstream press has been a very malign influence — extreme bias coupled with extreme ignorance (of just about everything). It still has huge influence — I can only hope that more and more average people figure it out and reject these buffoons.

By the way, Alex Berenson is a suggestion for another interviewee, relevant to my above comments on the press in general.

The stark inconvenient fact remains that unless we do something to limit by common consent the exponential and unsustainable growth of the human population we will outgrow the planet’s ability to sustain us and other forms of life. This is now so obvious to anyone who cares to investigate.

‘Extinction Rebellion’ may have alarmist disruptive and contradictory ways of showing it but they are right!

Are people really looking forward to a UK with a population of 120 million` and the “quality of life “that means for us all?

So how can we prevent it without world Governments accepting a policy directed by the UN, which currently is going-for-broke in population terms.?

Perhaps the Leicester surge just means that the process has been speeded up, and a lot of cases have been brought forward. In other words, there may be Leicester deal with in the future.

Huh! Appears as if UNHERD is not liking what I had to say about this diatribe by this so-called “journalist”.

Bill, try posting again. I’ve had a few comments simply disappear in the past, and like you, feared censorship, but I posted them again and they were published just fine. I still have faith that the Unherds are among the last of the Free Speechers (unlike Consortium News recently, which disappoints me utterly).

Interesting and persuasive.

Trump is the last Old School recognisable Presidint that the crumbing US will ever see.

Eveythimg about his obsessions would have seemed just mainstream Republicanism in the 1950s but that America is gone as any noistallgic look through old newsreels and films reveals.

A country of full-employment, rising living standards, Law and Order clean streets, respectful behaviour, expanding suburbs, optimism and a “dream” – all go ‘west’ in the opioid drug stupors of Ohio the gun crime of Chicago and Detroit and every US city – the rustbelts, the crime levels the gangsterism the constant agitation and discontent, the war of the police, the contempt for history, the whipped up racism, the decay, neglect, and indifference, the new Tribalism – desperate lives without meaning driven by a consume or die philosophy of aspirational manic greed a corrupt, cynical, political system bought by obscene levels of corporate wealth – all signify this new dysfunctional America, lurching to nonsensical, unreasoned polarised extremes fed by a never ending growth of identity politics and narcotic use at every level of society.

Thirty years ago French sociologist Baudrillard saw America then as lost in obsessive, artificial consumer fantasies -the ‘death of culture’ as Europeans understood it – what would he say now ?

Trump is Canute – doomed to fail – BIden is simply abject surrender – his Open Borders and the rush of millions from the Hispanic Latin south, escaping the drug Cartels which run Mexico, or merely extending their remit to the US, will ultimately see the transformation – an end of this America, as it was conceived by now abused as “racists” Founding Fathers.

I imagine that the future will bring more confrontation, even low level fragmentational Civil War and the break down of all Urban order at some stage – it is difficult to see what else can happen – there are no “shock absorbers” left in this society. The Army could not intervene and the police are being neutered as we write. A manic, hysterical totally amoral, corporate stooge media drives up all the the pressures daily!

All the institutions that might sustain the state have been abused and tarnished – or captured by extremists.

Post Covid America in decline will not be a pretty sight and it will start with “China Joe” bewildered septuagenarian, Biden.

Trump would be wise to throw in the towel – at least he could then say “I tried to reset he clock, but they didn’t want it”.

David, where’s your blog?

As these younger infected people grow in number and subsequently recover, this will, of course, continue to reduce the overall mortality rate. If this continues to trend downwards until it more or less lines up with seasonal flu, then the entire lockdown response will have been shown to be flawed. A ‘protect the vulnerable’ strategy seemed obvious from very early on when the age discrepancies became apparent. Easy with hindsight, obviously but it will be interesting when the final data are in.

It’s really not difficult.

1. The Leicester Pillar 2 data is, for a start, unreliable, and opaque. The more reliable and controlled Pillar 1 data shows no evidence of a ‘spike’, and countrywide, the disease has consistently followed Farr’s Law, declining way below levels that may be termed ‘epidemic’. It is also, remember, a mild disease (often asymptomatic) for the majority of the healthy, younger population, and fatality rates are falling.

2. The explanation for the age shift is because a large vulnerable population, with comorbidities was affected at the peak of the epidemic. The size of this group was abnormally large following an exceptionally mild infection season in 2018/19, with many more surviving into this following year.

Consequently, the data for deaths, was heavily skewed towards the older age groups that contained the majority of the vulnerable population. On top of this, of course, has to be considered the multiplier caused by the revision of post-mortem registration of deaths and the exaggeration of the role of Covid-19.

A further confusion is of the term ‘cases’ ( possible evidence of a viral presence) and ‘infection’ (actual illness). The lack of rigour in Pillar 2 testing is particularly susceptible to error.

As Farr remarked of infectious disease :

“The death rate is a fact; anything beyond this is an inference”

The death rates are quite clear, and broadly match the evidence of Pillar 1 testing. The data indicates no ‘spike’ or ‘wave’ or any other such modeller’s mythical beast. In fact, the current situation seems to turn Farr’s prognosis on its head :

“Inference is a fact. Death is an unfortunate contradiction”

As an addendum to my comment, I would highlight the age-related graphs of mortality on the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine website :

https://www.cebm.net/covid-…

The two features mentioned stand out :

1. The striking age gradient of overall mortality

2. The logical corollary of a decreasing elderly and vulnerable population as a consequence of this massive age bias in the effect of the virus.

I have little doubt that the tale of covid will in time present a different story than the one current on main stream media. Putting aside simple nuances, we have entered an interesting time of collective madness. Looking at the history of infections should inform us, but this does not appear to be the case. We have lived with infections from the beginning of human kind and should not be surprised about current outcomes – part of the cycle of life? To the susceptible many a virus is nasty. Then consider this – some 8 million people die a year because of malnutrition and diseases related to it. Were’s the moral outrage and horror at such a death toll? A tragic irony and hints at the need for perspective about all that we have witnessed hitherto. I recently lost a good friend – a lovely man who’s chemo therapy was stopped because of covid. Robbed of more life? A relative experiencing awful hip pain because their hip operation was cancelled and a good friend likewise. My daughter’s education annexed just as she preparing for her GCSEs. Futures and lives negatively affected by the decisions a Government makes, driven by the media and not by the virus itself.

I avoid the media most days and just dip in periodically. When I do indulge myself I despair at the lack of rationality and logic. Alarming increases in infections, mind 8 out of 10 residents of care homes tested, in a survey, appear to be asymptomatic! Okay in different articles, but the same news paper. The Vivaldi survey outcomes were tucked away at the bottom of a page. Speaks for itself.

The whole lockdown thing was supposed to be necessary to buy time so emergency services etc. were not overwhelmed. Sensible enough at the time. Seems to have worked, they’re not being overwhelmed, so that reason is gone.

So logically if lockdown is effective, then when you stop, cases are going to go up. Like standing on a hosepipe. Meaning that unless you’re willing to do it indefinitely – or spasm in and out of lockdown every time there’s a ‘spike’ in someone’s numbers – then sooner or later you’re going to have to take your lumps. A post-loosening increase is not a second wave, it’s a first wave that lockdown has postponed. And if a certain proportion of the population needs to be infected before herd immunity is reached, then for goodness’ sake you’d want it to be the least vulnerable. We should be encouraging young people to go out and mingle with each other.

A second blanket lockdown that includes youth and children doesn’t make sense.

I don’t know how anyone can be that level headed at 24. I can’t say I was.

I read these entries in The Guardian live blog yesterday. Someone hasn;’t got the memo, I thought. It included a link to the said document.

Needless to say, the entries disappeared a few hours later.

1d ago

08:02

Something else the report shows is that in Leicester, new infections are concentrated in a few areas and focused among children and working-age people. It points out that the “evidence for the scale of the outbreak is limited and may, in part, be artificially related to growth in availability of testing.”

Updated at 8.33am BST

FacebookTwitter

1d ago

07:57

So. Looking at local lockdowns – the other issue dominating the news today. The government last night slipped out the “rapid investigation team” report. It’s the motherlode of data that informed the decision to impose further measures in Leicester.

Interestingly enough, the report isn’t all doom and gloom. Less so, actually, than the news reports suggest. A table of the local authorities with the highest infection rates shows Leicester with 135.7 new infections per 100,000 people in the seven days to June 27, compared with 6.7 for England as a whole. The rate had decreased from the previous week but not very much. That’s not ideal, obviously – hence the the Leicester lockdown – but what’s interesting is that the other local authorities on the list had much lower infection rates: the next highest local authority on the list is Bradford, with 42.8 new infections per 100,000 people. In contrast to Leicester, their rates had almost all dropped by more than 10% compared with the previous week. Doncaster and Bolton are the exception to that trend: their rates had risen 10% – albeit, it’s worth noting, from relatively low levels.

The Telegraph, the only paper to clearly frame the report as showing progress, quotes former Tory leader Iain Duncan Smith branding it “very good news”.

I look at the numbers every day, and I wonder, why so many people in the community even get tested. Only 15% or so of the tests carried out the ONS states are positive. So how many people have been scared into this and are hypochondriacs? And we should really differentiate between testing for virus present and being ill. As with flu viruses, this one will eventually – hopefully – runs its course, and the more young people get it now, so better.

Trump looks ill.

Just sayin…

What you’re seeing is disgust in Trump’s demeanor. This is a guy who is a ‘builder’ by nature & nurture. No doubt, he hates to see the LEFT tear down the country. And I think a large part of the country is with him on this.

More testing = more discovered cases surely?

Comment from David Spiegelhalter on Leicester…”Fascinating and detailed PHE report on Leicester

https://assets.publishing.s… “if an excess of infections has occurred then it is occurring in young and middle-aged people”

Suggests limited impact on mortality.”

It is not clear to me whether these cases are actually new or whether we are just finding cases where people were infected weeks or months ago and are now no longer infectious. Probably both to boost the numbers and aggravate the fear amongst the uninformed. Whatever. The more cases, the closer we get to herd immunity.

I follow the German numbers closely, where numbers for smaller areas, like a large town, a council, are published by the RKI every day, since the beginning. Places which had no virus for 2 weeks, suddenly show a new infection. Either the person travelled, had the ” misfortune” to come close enough to an infected person, or they have been harbouring the virus for a longer time before showing symptoms. In North Germany, where I am interested in, the overall rate is so small, that the likely hood to bump into an infected person is so small, I think it might be a slow grower in some people.

I’ve been listening to this guy lately. He’s great. Very calm and measured. A real voice of reason and sanity.

He also recommended the book White Guilt by Shelby Steele. Incredible book. I nominate it for the Pulitzer. Seriously, that good.

https://www.bbc.com/news/he…

I can’t help but think that this meme of “Trump dropping out of the race’ the is the number one Democrat ‘wet dream’. There’s no indication that Biden will win at all – the polls mean nothing, not only at this point, but look at the past election polls as well – many conservative refuse to answer pollsters. Moreover, Biden has lots going against him; his repeated racist remarks, his 48 years as a politician will little to show, his mental feebleness, his inability to articulate a vision, etc. This show is just beginning

Sounds so interesting, I bought it on Kindle as soon as I’d finished reading. Very much the sort of thing I should have read earlier, when I started feeling uneasy about things myself.

My guess even a Substandard Trump will trounce Biden and his demented backers in 2020.. If biden Wins he will try to save Globalism vision..really nightmare of Soros,Bezos,branson,Gore etc..and CNN,Sky,BBC,ITV etc..& EU ”obamas Warning ”UK will b e at the back of the queue” Will Give Boris Johnson the Chance to rebuild uK high streets, and Manufacturing, the SARS2 pandemic showed the Danger of depending on China,for most Manufacturing (Apart from Food) …Seeing how Repressive China has become with Hong Kong means Biden wouldnt have a Clue,and be A puppet of Democrats like Nancy Pelosi,Elizabeth Warren..So Trump is lesser of Two…..If not then Dystopian ‘Assault on precinct 13” type inner cities warfare looms!

TDS suffering BBC journalist confuses what he wants to happen with reality.

Nothing new at all. Racial eugenicist progressives flourished in the early 20th century, literature from whom inspired Hitler.

If female prisoner sterilization is an arm of eugenics, then don’t forget Margaret Sanger, a vociferous eugenicist, and founder of Planned Parenthood, whose facilities now exist overwhelmingly in black and brown neighborhoods.

Yet another fantastic interview Freddie. You are far better than so many of the MSM equivalents who get paid mega bucks for doing a far worse job.

I never knew BLM was something started in 2013 with nothing but good intentions. It has now transformed into something which is becoming more and more contrary to its initial well intentioned aims.

It therefore fits neatly into my philosophical theory, which I describe through an electromagnetic spectrum and undamped pendulum analogy.

The EM spectrum is a fact of nature. There are bits we can see and bits we can’t but know they are there and make use of them for good. So we have radars, microwave ovens, mobile and satellite communications and infra red lasers and detectors, all of which are good and useful but harmful if used incorrectly. From that we get mobile phone mast and overhead electric cable type irrational fears with real accidents which tend to confirm those fears. In the visible spectrum we have our favourite colours but we generally like what can be done by mixing all of them. Beyond that we have UV, X-rays and Gamma rays. Again all useful and potentially good but also can be extremely harmful and again there are the irrational fears with real accidents which tend to confirm those fears.

When there is too much going on in the invisible spectrum (we all know it is there and we can all detect its effects if we look for them) and real harm is being done regularly, then there is a need to swing the pendulum back to the visible spectrum we all like, whilst accepting that low levels in the invisible are not harmful and are indeed good when under proper control.

This is what Marx was saying in his theories (which were intended for the rapidly industrialising countries of his time like UK and not Russia) and it is what Woke initially started as and what BLM was about and a whole host of other change things for the better ideas are all about. The undamped pendulum effect can be seen in what then happens as the pendulum gathers momentum and over swings the visible spectrum. We can see that in what Marxism became in the former Soviet Union and Maoist China. Once the pendulum has gone too far there becomes a growing force, again quite natural (with a pendulum that force is gravity) to slow it then bring it back. Undamped, the pendulum swings back and forth forever (perpetual motion does not exist because of friction eg air resistance, so eventually everything should settle). When the pendulum starts to hit the invisible spectrum on the other side we get things like iconoclasm – seen many times in history. And when it gets even further we get bloody revolution which often leads to bloody counter revolution. Whist things never follow the perfect sine wave of a pendulum, I believe you can map most things in human history into this analogous model.

What we need to get better at is damping the pendulum so it does not swing to extremes and settles more quickly. I think the way MSM behaves amplified by most social media makes the problem worse. The sort of rational debate and great Freddie interviews we get here are a key part of the solution. Would pushing unherd more into the main stream be the extra air resistance we need or would it suffer from its own undamped pendulum effect. Ie can we really modify human nature for the better or are we just like the other natural forces and doomed to swing from one mass bloodshed to the next? Given the undeniable fact that our planet can only sustain a finite number of us over the long term, is the bloody nature of human nature itself the natural corrective force we need until we can colonise other planets? Or maybe the answer to life the universe and everything really is 42 and I just have just had too much time on my hands during lockdown.

The riots are lead by left wing extremist anarchist of XR, BLM and trans-women are not elite even if they believe they are and low grade education with worthless degrees does not make them better informed than the average citizen. These people are marxist or mao extremists and no special status should be given. They are thugs.

Not convinced by the arguments.

“One of the doctors involved defended the cost to the state: “Over a 10-year period, that isn’t a huge amount of money compared to what you save in welfare paying for these unwanted children ” as they procreated more.”

Have to admire that honest expression of attitude from the doctor….not a million miles away from the idea that you should only have children if you can afford them.

Whoah! That’s a slippery slope, my friend…..

Comparing the situation of DD with that of the Eighur minority conflates two very different issues.

Children are a privilege, not a right. Sadly, we require more checks and assessments of those who acquire a pet than we do of those who birth a child.

When a woman proves categorically (6 children taken into care!) that she is not capable of caring for a child, it is quite correct to consider whether to revoke that privilege, particularly for someone lacking the mental ability to competently consider this matter for herself.

When combined with the certainty of death, and the inability of the woman to competently consider her own health , then it becomes reasonable to appoint a medical/legal officer to act in the best interest of the woman. This is the principle supporting a Power of Attorney, adult care of a minor and many other legal situations.

To compare the situation of DD to the forces sterilization of the Eighurs is to conflate two very different principles thereby detracting from the plight and genocide facing the Eighur people.

That was actually her whole point. As horrible as the DD case was, she was reluctantly agreeing that in very rare life-threatening cases there is probably a case for forced sterilisation. She was highlighting this by contrasting it to the tragic situation of the Uighurs.

The testing has no provenance – because of the contaminated primer harvested from the lung tissue of the survivors in Wuhan, and the nature of how the RT PCR tool is misused.

Because of the nature of the contaminated primer (lung tissue, sputum, puss, to name a few — and no virus isolated according to Koch’s postulates or modified River’s protocols) not to mention the arbitrary numbers of repetitions which yield grossly flawed results — the covid19 “test” is not measuring anything with a shred of validity.

It’s a false premise from the very start.

Therefore any figures and/or any conclusions whatsoever based upon the testing is based upon a straw man argument and is therefore utterly fallacious.

At the back of herd immunity is the foundation of reliance on our natural immunity and how we can wholly enhance it, rather than a supposition that our only hope, only option is to assume that health comes from a manufactured vaccine.

The discussion of other medical treatments holding out promise needs to remain in an open clinical debate.

We don’t need to irreversibly create 7 billion cytokine storms for which we cannot connect the dots later, if there’s anyone left to connect the dots, as whenever a SARS Corona vaccine was tried in the previous animal trial – all of the animals at first developed antibodies to the vaccination antigenic agent but then later — all of the animal test subjects died — when exposed to the wild virus when it was encountered (due to disease enhancement cytokine storm) and the trial was immediately halted.

Here are some references:

https://science.sciencemag….

https://www.sciencedirect.c…

https://journals.plos.org/p…

The “test” has no provenance. Basing our entire futures and outcomes upon a false initial premise? It’s not good enough.

I came back to add one more reference to my original comment.

4th reference regarding the problems associated with Kary Mullis’s RT PCR tool when it’s applied to clinical testing:

https://www.nature.com/arti…

The propagation of the Panicdemic ‘Fear All’ narrative has been one of the key features of this weird episode in the life of the UK.

Some light relief is needed, and, if you have a wry sense of humour, this attempt by Paddy O’Conneli (BBC : ‘Broadcasting House’) to steer an interview towards the House ‘Panic’ narrative, in the face of a succinct proportional and rational analysis, is fascinating :

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sound…

Begin at c. 17m 54s

Great article, would’ve liked to have seen a mention of Buck v Bell, the 1927 supreme court case that legalized forced sterilization and has never been overturned.

I think I would rather take the advice of medical professionals and epidemiology experts than a journalist with an agenda.

What an apposite pseudonym!

Don’t be so naive. One epidemiologist only has to open his/her mouth for another to condemn them. Additionally most, but not all, tend to be inarticulate’ geeks’, or fantasists, like the recent Ferguson creature.

We rely on somebody like Freddie Sayers to read and synthesise much of the preposterous drivel vomited forth by the ‘new gods’, the medical profession, and then give us his considered opinion.

Your criticism implies that Mr Sayers sits in a darkened room with a wet towel around his head, and just ‘makes’ it all up.