E-government naturally favours the young (Photo: Mark Kolbe/Getty Images)

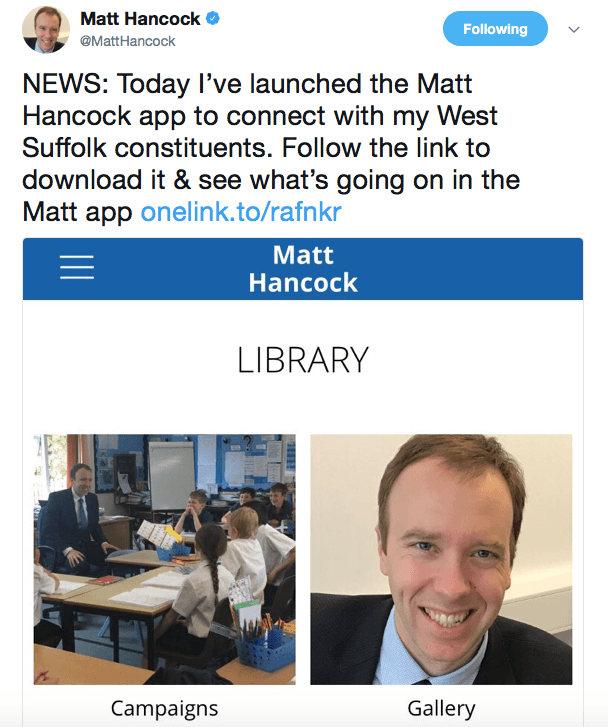

The recent launch of the app from the British Minister for the Digital Economy – which allows anyone who downloads it to connect up with the West Suffolk MP – was greeted with some ridicule. But while those sniggering may have noticed certain privacy issues, they obviously hadn’t grasped its greater importance. In fact, Matthew Hancock’s new social media service was reflecting a digital approach that had been some ten years in the making.

Hancock had set out his stall a couple of years earlier in a speech to the CPS1. Contemporary politics, he said, was split between left-wing reactionaries, such as Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, and right-wing reactionaries, a la Farage and Trump; both “obsessed with recreating a better yesterday” and both seeking “false certainties” that are no longer there. But the future, he said, for his party and for global capitalism lay in an unflinching investment in technology and the culture of disruption emanating out of California.

Hancock’s intense optimism in the digital revolution placed him among a new breed of British politician, the ‘Uber Cons’, who recognised in the digital revolution the potential for Conservative principles to be realised once more. These ‘UberCons’ were libertarian in economics, metropolitan in values and embraced a form of globalisation which is not burdened with old imperial guilt or even eurosceptism – and they were obsessed with emerging markets and restoring Britain’s innovative tradition.

Their rise dates to George Osborne’s pilgrimage to Silicon Valley, in 2006, from which he reported excitedly:

I have seen the future and at present Britain is not part of it…. we may have invented the internet but it’s the Americans who have colonised it. It’s time to stake our claim.

Osborne was true to his statement. And his tech strategy has been a great success; comparable in scale and speed to Thatcher’s deregulation of the City of London in the eighties. Digital is now worth 7% of the UK economy and is growing at a much faster rate than the rest of it.

But an equally significant part of the story was how Silicon Valley thinking could disrupt the British state and public services. A thriving digital economy and the development of e-government could reduce public expenditure and extend consumer choice and responsibility. Likewise, it was hoped that embracing flexible working models (unbeholden to unions) and the sharing economy would enable the twin pillars of Conservatism – entrepreneurialism and voluntary spirit – to thrive.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe