Cyborg hands. Credit: Getty Images

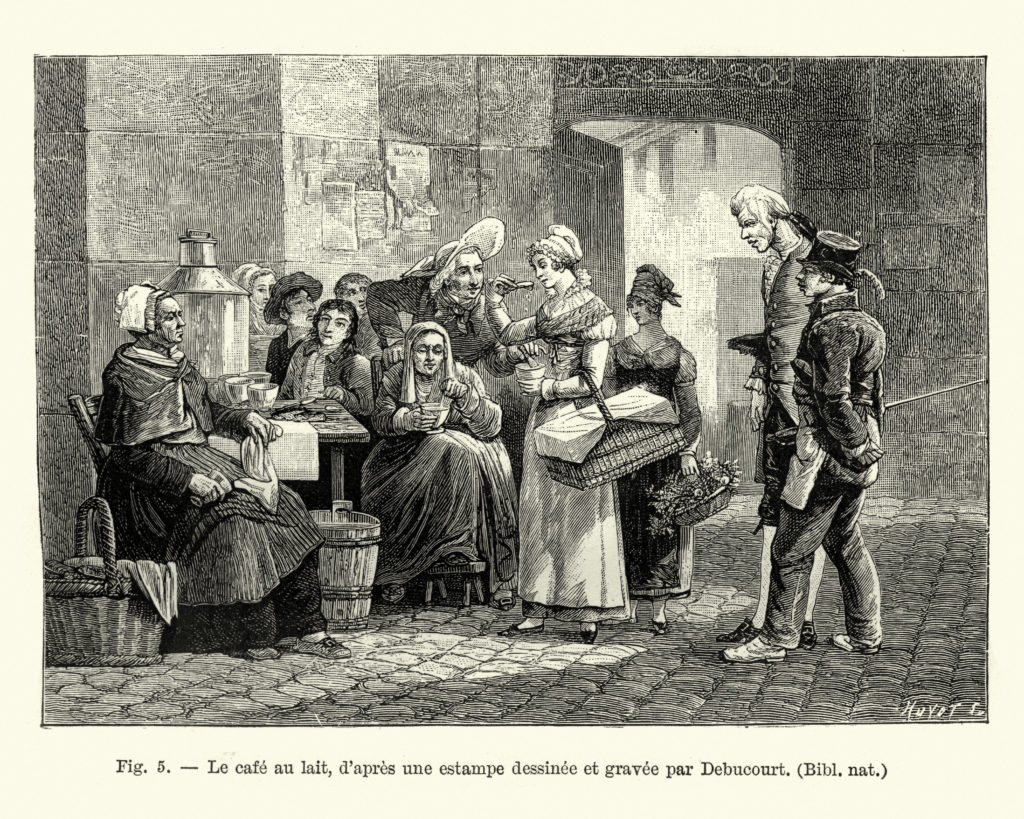

Ever since I read Nigel Cameron’s fascinating book Will Robots Take Your Job? not a day passes without wondering why I do not hear a steady ‘clip-clop’ or have to step around piles of horse manure in the streets. I’ve even bought two histories of the horse as my Christmas reading, though I haven’t been on a horse since I was eight.

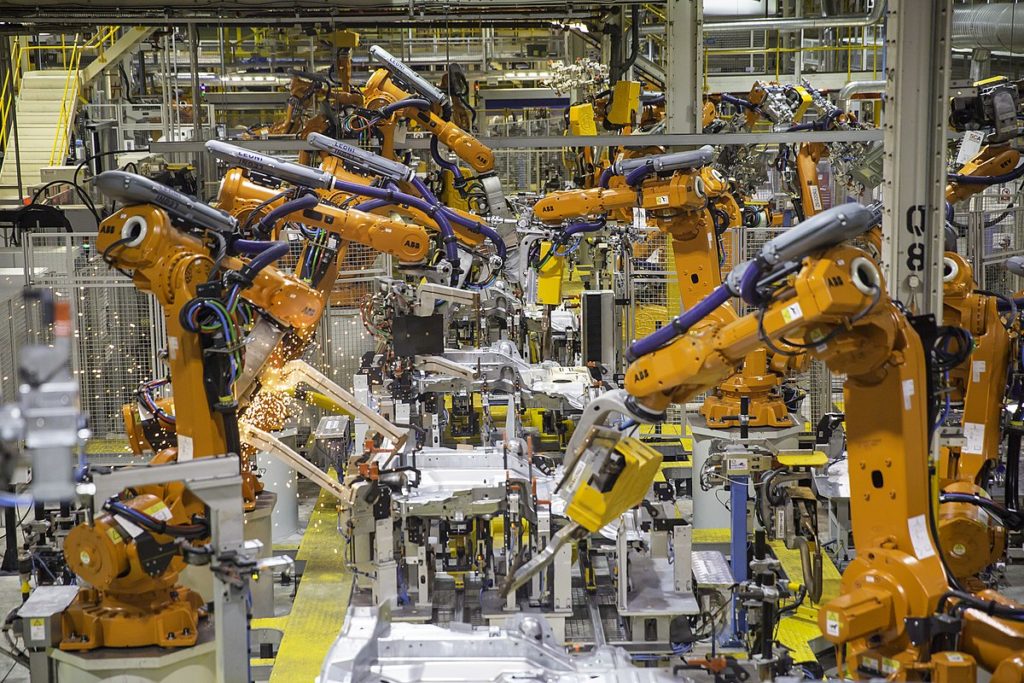

A major anxiety is whether, in line with the slower-paced First and Second Industrial Revolutions (the Third was digitalisation), artificial intelligence (AI) and robots will render swathes of humans superfluous, though the latter will surely not be converted into dog food in remote plants.

Rather the concern is that in a new age of jobless growth, millions of people will no longer work any more. Being unable to respond to the usual social conversational gambit ‘and what do you do?’ will be the least of their problems, though if Jeremy Corbyn is elected we’ll be able to say ‘we hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon and literary criticism after dinner’, as Marx once prophesied.

Their sense of self-worth, and quite possibly the integrity of families, will collapse, whether or not these people subsist on the universal basic income which some have proposed; so will traditional social contracts based on reciprocal labour and reward, especially when people are in need. Various (self-interested) prophets of the new societies that Industrial Revolution 4.0 will create imagine a shiny (almost early Bolshevik) utopia. The reality may be pockets of that, walled off from the decay and degradation beyond, as more and more people are ‘left behind’ in ‘flyover country’.

Although the broad contours of Industrial Revolution 4.0 have been known for some time, it is striking that in the UK it is only recently that politicians have begun to address the profound consequences.

The Conservative MP Alan Mak chairs a new all-party parliamentary group on the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Being Anglo-Chinese, Mak is acutely aware of what happened to the world’s largest 18th-century economy when the Qing dynasty’s Qianlong Emperor told western emissaries that he ‘had no use for your country’s manufactures’. Contemporary China is determined not to make the same mistake twice, with a huge $125 billion programme of investment in 3D printing, AI and robotics.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe