Last summer, I interviewed the philosopher Peter Singer for a radio programme on a growing ethical movement known as effective altruism.

Singer argued that we ought to calculate moral regard in such a way that we treat all people the same way, irrespective of how close we are to them – irrespective, that is, of whether they are members of our nation, group, or even family.

As he was speaking, I couldn’t help thinking: “I bet you give rubbish Christmas presents to your kids.” I mean, if you treat all people the same, then there is no reason to prioritise gift giving to your nearest and dearest over against a total stranger in a far-away country.

Singer is an extreme example. So extreme, that he believes that even our preference for human beings over and against other sentient beings is a form of moral parochialism. For him, pretty much, the most effective way of reducing suffering to sentient beings – the essence of morality in his book – is to give all you can to liberate chickens from factory farming. If you use your money for anything else, you are guilty of a form of speciesism that prioritises your own kind over the obligation you have to reduce suffering universally.

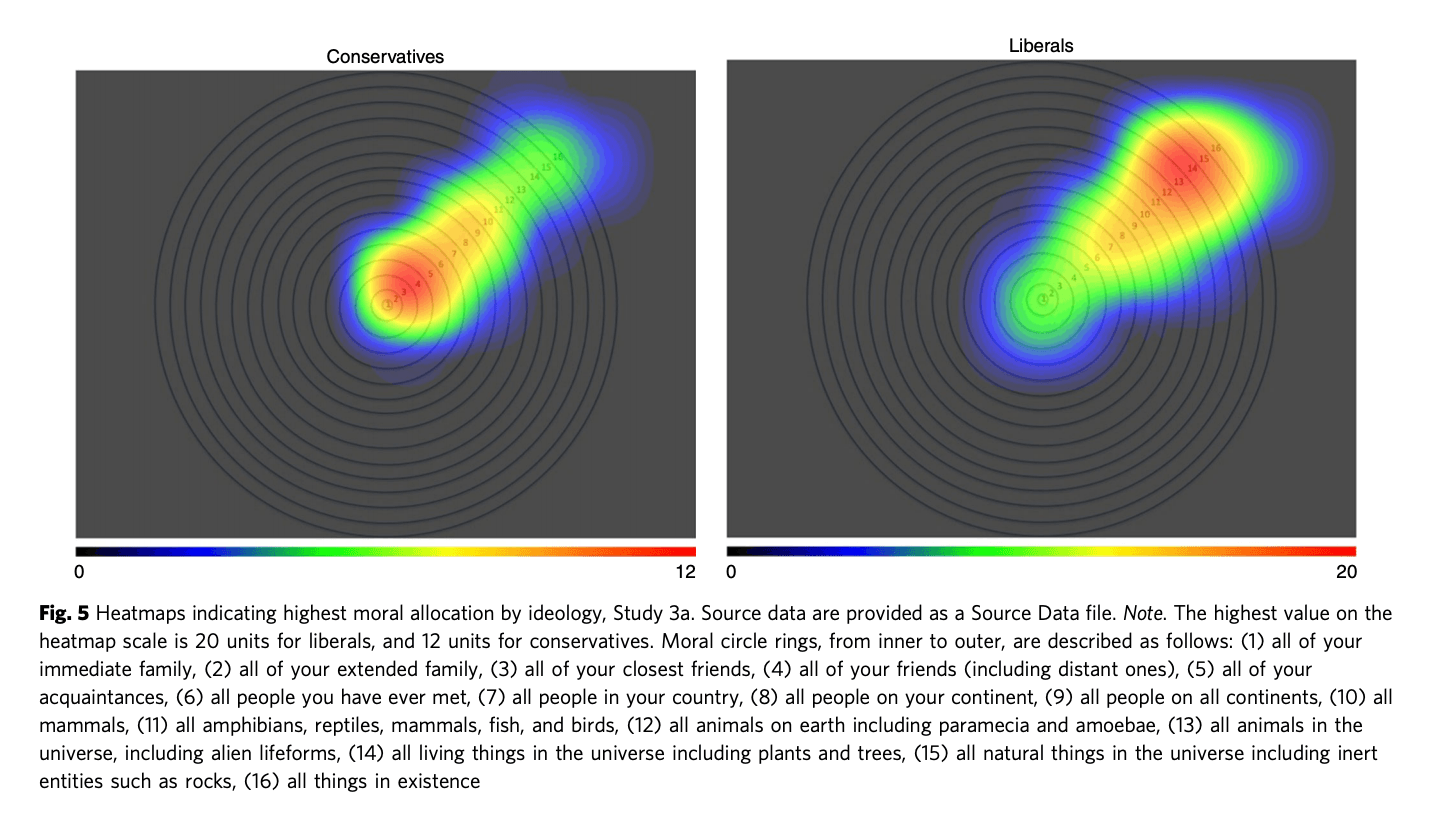

In a fascinating new paper, Jonathan Haidt and others have brought together a number of studies that have linked our broad moral and political commitments — whether we are liberal or conservative — to whom we prioritise for moral concern. Over a number of empirical studies, it is demonstrated that conservatives are more parochial in their moral regard — family and nation first — and liberals more universalist, extending, at the extreme end of the spectrum, to treating human and non-human suffering on the same level, like Singer.

The question here is whether compassion is properly a general instinct that should apply equally to all, or whether it is always necessarily specific and partial? Is compassion a kind of rational calculation, treating everyone, every sentient being even, as a unit of one? Or is it more like romantic love, something that makes little sense in abstract terms and which instead grows out of one’s reaction to very particular and specific attachments?

For Haidt, this paper is a part of a much broader project – see The Righteous Mind — to try to explain liberals and conservatives to each other. He concludes:

Like Brexit.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe