Drop what you’re doing and read this: it’s one of the important pieces of opinion research this year.

Entitled Britain’s Choice, and published by More in Common, it doesn’t analyse Britain by political affiliation, but according to deeper values. So instead of Left versus Right or Remain versus Leave, we are grouped into seven tribes including “Progressive Activists”, “Established liberals” and “Backbone Conservatives”.

By getting to the heart of what people really believe, this methodology picks up some much bigger differences of opinion than those revealed by more conventional categories like party affiliation.

So, does this research show Britain engaged in a bitter them-and-us culture war? Not quite — and, in many ways, not at all.

For a start, the seven groups don’t always disagree along the same lines. The combination of groups on each side of the argument varies from issue to issue. Then there are the issues on which there’s a remarkable degree of unity. For instance, the majority of people in all seven groups said they were “proud of the advancements we have made in equality between men and women”. The research also shows a seven-group consensus on issues like localism (too much is decided in London), climate change (a concern for us all) and racism (a serious problem).

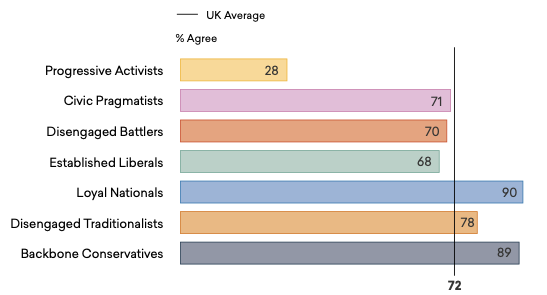

However, on one issue a culture war does appear to be raging. While all seven groups agreed that hate speech was a problem, only six thought the same about political correctness. The outlier on this issue is the Progressive Activist group — only 28% of whom thought PC was a problem, far behind the next wokest group (the Established Liberals) on 68%.

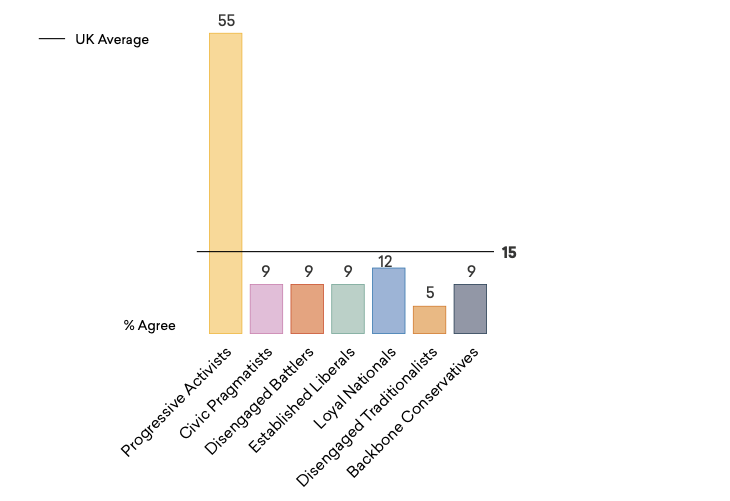

Now consider this finding alongside another — which is that compared to the other six groups, the Progressive Activists were roughly five times more likely to share their political opinions on social media. In other words, an unrepresentative group with unrepresentative opinions on a controversial set of issues is having a disproportionate impact on the national conversation.

This risks becoming an even bigger distortion if the mainstream media becomes unduly influenced — especially in an attempt to keep a younger audience. In particular, the BBC could do itself serious harm if it panders to a group that is so out of kilter with the rest of the country. It’s not as if our national broadcaster is in an unassailable position these days. Technology is changing the way we consume media and the legitimacy of the license fee is now in question.

The Corporation should also pay attention to something else in the Britain’s Choice report. When the public was asked to choose three things that made them proud about the UK today, only 7% picked the BBC. That compares to 14% for the monarchy, 20% for the armed forces, 29% for the countryside and, right at the top, the NHS on 57%.

If the BBC wants to stay relevant then it should focus on the things that unite us as a nation — and not on becoming the broadcasting arm of Twitter.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeAs Tim Pool and others have endlessly pointed out, only about 2.2% of the population is ACTIVE on Twitter. (About 20% of people have an account but have better things to do). A majority of that 2.2% are SJWs etc, which utterly skews the conversation and debate (to the extent that it can be termed a ‘debate;). The result is a gaping and growing chasm between the media/political industrial complex and the rest of us.

It seems odd that the BBC chose the M&S business model that alienated their core customers while putting all their energy into competing in a market they had little chance in gaining.

Surely the BBC should embrace diversity (which they constantly ram down everyone else’s throats) and stop recruiting young middle class “group thinking” arts graduates for a while.

There is absolutely no chance of that happening. The BBC now exists solely to provide jobs for the middle-class arts graduates you mention – across all races. It simply has to be defunded.

If that sentiment appeals to any reader, then defundbbc.uk is a site worth visiting …

“Diversity” is code for anti-white.

Diversity is about recognising that everyone is different and that having a range of characteristics in a team has benefits – diverse teams do better that non diverse teams.

Inclusion is about making everyone in the team feel valued so you can get the best out of them as individuals contributing to the team goal.

That both these ideals have become twisted by “woke” administrative bureaucracies into what we see today as D&I is very sad. Most of society’s problems would largely dissolve if we could genuinely embrace the true meaning of D&I. Sadly we are marching further away from that ideal every day. Hopefully the pendulum will swing back before we either have a race war or achieve the Orwellian nightmare.

Unfortunately diversity no longer means diversity of opinion or thought.

Indeed that is the Orwellian nightmare we are blindly marching towards. Even those of us who realise it are being progressively rounded up, having yellow stars put on us and being marched through the gates. The only question is what perverse wording over that gate will replace “arbeit macht frei”

Some of the questions in this survey seem transparently slanted to elicit a particularly response. Take, for instance, the question about how we should respond to the pandemic. “I mostly just want things to return to normal” uses the word “just” to suggest that this is a limited, unambitious, unenterprising aspiration. “We should seize the opportunity of COVID-19 to make important changes to our country” defines those potential changes as positive, while “opportunity” is not the first word I would have chosen to describe an epidemic. I wonder if the answer would have been different if the wording had been “We should respond to the COVID crisis by making radical changes”. Likewise, would more people have favoured “returning to normal” if the response had read, “I long to recover our normal freedoms and opportunities”?

I couldn’t help wondering, given that this question was part of a survey of different countries and given that the Netherlands and Poland were less keen on change and more eager to get back to normal, whether the wording was different, less rhetorical, less positive about change, in the relevant languages.

The mere mention of racism and hate speech told me how this is slanted so I stopped reading. And as for 57% revering the NHS, an organisation which has been failing us all since the start of the COVID nonsense, it beggars belief.

The NHS has been failing us for a lot longer than that.

The question is: what are you most proud of about Britain. That 57% said the NHS is the thing they are MOST proud of tells you a lot about Britain today not about the NHS.

Given the almost religious devotion to the NHS that has been rammed down our throats over the past few months, this result is hardly surprising. It will be interesting to see how it changes over time. Especially as people wake up to the fact that the underlying drive behind the re-imposition of largely ineffective COVID restrictions is the fear amongst politicians that the NHS will collapse this time – it came close last time. Sweden’s far less restrictive approach is founded on having a healthcare system which did cope well last time and will continue to cope even better this time

The heads of PHE and the NHS should be removed and the entire edifice remodelled, removing the multiple organisations within it and disposing of the layers of bureaucracy.

The Government has failed us not the NHS if the NHS has failed its due to lack of funding due to austerity which again lays in the hands of this Government.

Racism is becoming a problem; thank you BLM!

A lot of the problem is ‘perceived racism’ as perceived by the likes of BLM and Harry and Meghan.

Do wake up support BLM and through it the Democratic Party in the US which evolved from the old supporters of the Cotton Plantation Owners.

I’m sorry – support Marxist, anti- capitalist, BLM?

Support the Democrats whose petty spite at losing the last election coupled with their consistent failure to maintain those cities and sections of America they do have ‘control’ of has allowed the divisive BLM, Antifa etc to run riot in the US, burning, looting and murdering as they go?

‘Perceived’ is subjective, hence the current madness not only in the UK but mostly across the west thanks to the GF incident. I would like to ask all the knee takers, footballers,

Lewis Hamilton, policemen why they weren’t doing this before. Says it all doesn’t it!

Don’t tell me, two of the survey questions were “Do you engage on social media?” and “Do you believe political correctness is a problem?”, and only THEN did they bucket you accordingly

The central message of this report seems to be that, although we tend to fall into certain different types, we have more in common than divides us and, if we so choose, we should be able to ‘muddle through and find compromises and solutions which may be imperfect but move us forward’. Which I suppose is quite a laudable aim and sounds quite British.

On the other hand, I didn’t think that my personal views fitted with many of the beliefs which it said the majority supported. For example, it said that a majority of all types agree that racism is a serious problem. Nevertheless it was good to see that a majority of all types, except one, thought that political correctness is a problem. And also good to see the realisation that a minority ( Progressive Activists ) have a disproportionate impact and should be listened to less.

I did wonder whether the report was deliberately done in such a way ( using leading questions, perhaps ) as to reach the conclusion it did ( that we have more in common, etc.. ).

Nevertheless, I found it interesting.

I’m sure you’re right in saying that we have more in common than divides us, but the entire media wish to grab our attention, which is much more easily achieved by reporting on disagreements (think of the many punchy and combative words employed) than on the agreements. Indeed many television programmes invite people with the very purpose of disagreeing.

This is only natural, but does tend to make us think that there is more disagreement than otherwise. It’s probably unavoidable, given free speech and democratic competition.

I started reading the report at the link. But when I got to the bit where it described the 7 groups, I did not fit into any of them. There were some that I definitely did not fit into at all (progressive activist) and bits of others where I did fit. But even taking the bits of the groups that I did feel fitted and making a mixy group, I still did not feel I fitted perfectly into it.

That, I guess, is the fundamental problem with trying to group people. It will always cause as many problems as it seems to solve.

I would like to see more on how the research was done and how many people were involved in this study. All I can say is in my own experience I have found the majority of people just believe whatever the establishment media tells them to believe and the minority question everything with critical thinking.

It is bizarre that this research is used as a stick to beat the BBC. If it is true that the BBC is out of kilter with public opinion then these findings shows that it is not doing a very good job.

In fact when it comes to reporting news and current affairs it should strive to be impartial regardless of whether public opinion likes it or not. For example how much credence should it give to conspiracy theories that have no basis in fact, such as concerns about 5G? There is a problem where right wing politicians think the BBC is too left wing and left wing politicians think it is too right wing, so when either get in power they try and make the BBC in it’s own image. If you want to sort that out you need to set up a bipartisan group to oversee the BBC so that neither the left nor right can do that to the BBC. Any takers?

The BBC can by no stretch of the imagination be described as impartial. As former employees have testified, it is irredeemably left wing.

It has long since ceased to report the news. Instead it seeks to control and manage the news agenda to uncritically promote its own world view. This it does by carefully selecting which stories it reports and how it reports them while at the same time denigrating those who dissent. Witness its reporting (or non-reporting) on Europe, immigration, the Trump presidency and climate change.

As for the old chestnut about the BBC also coming in for criticism from the left, there are still some people to the left of the BBC and criticism from them does not make the BBC not left wing.

The BBC has had more than sufficient warnings and is incapable of change. It is staffed by people who are entirely convince of their own virtue, who share the same world view and who ensure that only the like minded get through the door. It needs to be scrapped and not replaced. There is no point in creating another state broadcaster staffed by exactly the same people or their anointed successors.

There is no such thing as political correctness. It’s a comedic trope used as a term of abuse along the lines of ‘health and safety gone mad’ and now ‘woke’. If the report shows that there was unity among the seven groups on sexism, racism and climate change then all seven support the aims of most of those characterised as politically correct. The research does not reflect what people feel or believe but how they respond to labels.

There is such a thing as political correctness if you are in the unfortunate position of being targeted by it.

Political correctness quite clearly does exist. I was first subjected to it back in the 1990s when my professor made me substitute the word ‘blackboard’ for ‘chalkboard’, due to the word ‘black’ having negative connotations. I argued that the word ‘black’ didn’t have negative connotations, but stopped when it became clear that continuing the debate with her would hinder my academic progress. I’ve experienced many other examples like this, as I’m sure others have on this website. I think the best way to summarize political correctness is when an authority figure imposes an ideology on another adult without permitting them space to debate or refute it, knowing full well that do so could incur a penalty such as loss of status, reputation or employment.

Inasmuch as certain types of people believe that hounding individuals out of their jobs, boycotting, no-platforming etc. are justified on account of the ‘wrong’-ness of their stated beliefs, it is clear that some political beliefs are held to be correct, and others not. I cannot understand the claim that there is no such thing; the left believes that certain beliefs are correct or wrong (literally that you can be politically correct or not), the right that the left is trying to impose this dichotomy (described unsurprisingly as political correctness) on everyone else . So that’s the right and the left believing in it. So how on earth is there no such thing?

It is obvious to the many apolitical people with whom I come in contact that there IS such a thing as political correctness.

I also feel obliged to comply.