Occupy St Pauls (Photo by Ben STANSALL / AFP) (Photo by BEN STANSALL/AFP via Getty Images)

I am Giles, son of Anthony, son of Harold, son of Louis, son of Mark, son of Morris, son of Jacob, son of Judah, son of David. All English Jews stretching back to the early 18th century. All Jews, that is, except for me.

That is my father’s family. My mother’s was comically different. “As goy as it gets,” a friend once remarked. Seeking to escape a dysfunctional and claustrophobic working-class home in rural Leicestershire, she dreamed of another life. Running away to become a nurse, she imagined something more exotic, well-travelled, urban. And her name for that became “Jewish”.

She had no idea what that really meant, of course. But when she met my father’s mother in her Golders Green flat, she marvelled that they said “darling” all the time and had carpet in the loo. This is what she wanted. But by then my father was already in full flight from his Jewishness. When Nazi bombs fell on London, he was evacuated to a small Christian prep school in Devon where they wore little pale blue crosses on their caps. The war stole his history. And we never spoke about it.

This was the joke of my family background: I have a non-Jewish mother who pretended she was, and a Jewish father who pretended he wasn’t.

It is nearly a decade now since all this buried history unexpectedly caught up with me. I had just resigned from St Pauls following the Cathedral’s decision to evict the Occupy movement from the cathedral precincts. And I was in search of a new job.

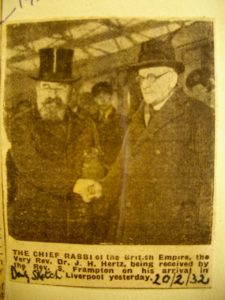

I had landed an interview in Liverpool, and having a bit of time to spare beforehand, I went to check out the synagogue that was just along the road from the Cathedral. I understood there was some distant family connection. Chancing my luck, I banged on the door, and was welcomed in by the caretaker.

There on the wall was a large oil painting of my great great uncle, Rev Samuel Friedeberg, who ran the synagogue for over 40 years. I stood staring up at his face for a good ten minutes. Then I left, filled with some weird and uncontrollable emotion. I had to stop and sit at the side of the road. All I could do was cry. And I really didn’t really know why.

The Friedebergs had arrived in Britain sometime during the reign of George I, which makes them among the oldest Jewish families in the country. Over time, they pulled themselves out of the ghetto in Portsmouth, and began to do increasingly well for themselves. They were constantly changing names, trying to fit in, trying to deflect the brutal anti-Semitic culture of the Portsmouth Point. Mordechai became Mark. Bilhah became Elizabeth. And eventually, Friedeberg became Frampton or Fraser.

Why had that paintings so affected me? A few months before the Occupy episode, I had been interviewed for the post of Bishop of Edinburgh. And I was asked “Where are you from?”, a once innocuous question that is now politically freighted. Identity politics has turned it into a threat, rather than an open invitation. I blithely explained the provenance of Fraser, that, no, it didn’t imply some deep Scottish connection. As it happens, I wasn’t all that bothered that I was not chosen for the job. But I was seriously disturbed by the question.

And I think seeing that portrait in the synagogue exploded the same buried question in my emotional life. Where was I from? Even my name felt made up: Giles — an attempt to claim some sort of poshness, chosen by my aspirational originally working-class mother — and Fraser — an attempt to disguise Jewish origins. It was like I, too, was made up, something confected, artificial. A lie.

What, then, of my Christianity? Was that also an elaborate disguise? Generations of my father’s family had struggled to climb their way into the establishment, to be more English than the English, distancing themselves from the more recently arrived Jewish immigrants from Russia. And what to make of Samuel Friedeberg — dressing up in clerical collars, mimicking the clergy of the Church of England, styling himself Reverend as many Jewish clergy did at the time? Being a Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral was the ultimate family triumph. And, for me, it didn’t work out. Disraeli once described himself as the blank page between the Old and the New Testaments. Queen Victoria didn’t understand him, but I do.

My attempt to reckon with this complex and conflicted past is going to be published this month. Chosen: Lost and Found between Christianity and Judaism is no doubt a curious book. “Part autobiography, part religious reflection, part ghost story” is how the journalist Paul Vallely has rightly described it. I suspect that many immigrant families will understand those tangled emotions that attend the desire to fit in with a new culture, the various adjustments that it requires, even the questions of betrayal that it sometimes raises. I, too, call the book a ghost story because my forebears come at me as ghosts, figures that I ignored for most of my life, and ones that have not received a proper burial.

It is a religious reflection, too, because of the curious hybridity with which I have struggled. And something that was baked into the very origins of Christianity itself — a religion founded by a Jew, whose first followers were Jews, and yet one that, within a few generations of its origins, was distancing itself as much as it was able from its Jewish beginnings. In other words, Christianity itself requires a great deal of unscrambling. Because in the attempt to ingratiate itself with the dominant Roman culture, Christianity is also the product of a kind of wilful forgetfulness of its past, a betrayal even. And intellectually, I think we are only just beginning to work this through.

But what sort of work is working it through? And how does working it through help? In 1915, Sigmund Freud — a secular Jew with a complex and ambivalent relationship with his past — published Mourning and Melancholia. The difference between these two conditions is crucial. Melancholia is the unconscious pain of buried loss, one that does not even know how to name what has been lost, or indeed is even aware that something has been lost. It is a kind of miserable stuckness where a kind of diffuse unspecified unsettledness seems to stay with you, wearing you down. Mourning, on the other hand, is the conscious attention to what has been lost, allowing grieving to take place. And eventually healing.

I think my reaction to that painting in a Liverpool synagogue was the first indication that something was wrong, that there was a pain of loss I was not even able to name.

Where are you from? I think any immigrant will understand the attempt to hide one’s previous commitments in order to proclaim oneself loyal to some new situation, that feeling of unnamed guilt as old loyalties are replaced by new ones.

And not just immigrants: social mobility itself, that totem of progressive politics, often means the abandonment of one culture for another.

But deep change is nonetheless unsettling. And some of it takes generations to work through. The Hungarian psychoanalysts Abraham and Torok speak of “transgenerational haunting” — our ghosts echoing down the family tree, often carried by the things that are not said, by our silences.

Little wonder “Where are you from?” remains such a threatening question.

Giles Fraser’s ‘Chosen: Lost and Found between Christianity and Judaism’ is available to pre-order now. It will be published on April 29th.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeGiles’ book sounds extremely interesting at a time when identity is such a volatile issue, and being from Giles it’s bound to be well-written too. The complex relationship between Judaism and Christianity isn’t explored nearly enough, in my view. But I’m surprised at his comment that Christianity “within a few generations” sought to distance itself from its Jewish origins “in an attempt to ingratiate itself with the dominant Roman culture”. As a Christian pastor he should know his early Church history well enough to appreciate it was far more complex than that.

The first Jewish Christians were expelled from the synagogues and forced to develop their own distinctive style of worship, centred around the Eucharist as both sacrifice and a paschal meal – while retaining many aspects of Jewish tradition, including priesthood, psalms, readings from the Torah and some Jewish prayers. The Jerusalem Christians were persecuted and many imprisoned and killed by their Jewish brethren. But the new faith was carried abroad to the Jewish diaspora all over the Greek and Roman world, and from those Jewish communities to their gentile neighbours. St. Paul, a Jew who had once persecuted the Christians, became an enthusiastic apostle to the gentiles. Soon the gentile converts began to outnumber the Jewish converts in Rome and elsewhere in the empire, and they felt no particular attachment to Jewish identity or legal customs. They particularly didn’t want to be circumcised! This began to widen the separation between Christians and their Jewish roots. Waiving the need for circumcision was nothing to do with ingratiating themselves with the dominant culture, but everything to do with accepting all who wished to believe, regardless of culture, ethnic or religious origin etc., as equally worthy of salvation.

The Epistle to the Hebrews is a wonderful example of how important the Jewish covenant and the Jewish scriptures were to these early Christians, and it remained in the canon for Christians of all backgrounds to read as sacred scripture from then till now.

Of course there were always tensions. Jewish Christians especially felt keenly that their non-Christian brethren had betrayed their Messiah, and rejected his message. Then after the fall of Jerusalem in AD70, and the disaster of the Jewish wars, there was a general feeling that God’s judgment had visited them – even though that was contrary to anything Jesus would have taught, and he openly forgave those who had him killed.

Then began the terrible persecutions by the Roman state, that went on for over two hundred years, and it was Christians who were the target, rather than Jews, who were considered less of a threat, tending to keep themselves to themselves and not actively seeking converts. So that led to further separation.

Christianity did indeed become over-involved with the state, much to its detriment, after the persecutions ended and to some extent ever since. But I think it’s too simplistic to brand this as a betrayal of its Jewish origins.

Thankyou Hilary. You have made a point I was planning to make far better than I could have made it.

Thank you for such an informative comment.

You are right; few people realise that Christianity is Jewish.

Jesus was Jewish, ..but only on His mother’s side 😉

Unreasonable to suggest his Father would step outside his tribe?

Is it? It probably is – it sure unleashes many further questions asking myself, such as “why am i not there where i’m from”, and “would i be rather there”, or “would i rather be someplace else” or “why is it here where i am” & so forth, and i’m not even sure of the answers to those.

I do get asked that question a lot, because my accent is thick and strong (a lot stronger than it comes across in typing). Initially it made me feel embarrassed (the easternbloc “second class” shame), but nowadays i say it with a beaming smile, as i became actually quite proud of where i am from. That pride grew simultaneously with my loyalty for England where i am.

In my old quarters of continental Europe being Jewish to any extent is a given for most. I know i am, just not quite to what extent. Then again, my nation’s ‘founding fathers’ took up Judaism at some point during the völkerswanderung, long before they took up Christianity after they finally settled for good where they did – so we all are bona fide Jews in a way, so to speak.

It is entirely possible to feel loyalty for several things (places, nations, religions, etc.) at once. JudeoChristianity is one item (and comprised of many more elements than its named halves suggest), not two mutually exclusive concepts.

Only for the culturally insecure arriviste social climbers, who don’t want to be reminded to where they climbed up from, for they are ashamed of their roots. A well-rounded individual feels at home in any milieu one happens upon. It is entirely possible to inhabit many ‘cultures’ all at once. Social mobility is not a one-way route.

A disturbing experience can be going to a lot of bother and pain to find ones roots, and try and carve out an identity or home there, only to discover that when you need that strength most you really don’t belong there either, you are still a sojourner. Not because it’s a disguise or you haven’t gone back far enough, but because that’s the human condition.

Giles and I share a certain kind of history, albeit in a minor way. I came to England from Hungary as a refugee at eight years old in 1956. My parents were Jewish, though my mother – having been through two concentration camps – denied it to save her children from the same fate. At twenty-one I was baptised by full immersion but the magic did not last and I regard myself as a secular agnostic now with some of the residual questions raised by Giles as to what a Jewish history might mean.

To the point. After all these years I still retain a trace of accent that is light but hard to place and have lost count of the number of times people have asked me where I am from. It is a question I have always been glad to answer because, despite the family history, I never regarded the question as the beginning of an inquisition. It seemed to me an expression of intelligent curiosity and it was nice to be asked.

I understand how it has become what people now call a micro-aggression and I can see why it might be regarded as such, but it was never aggressive to me. Indeed, I admit I have asked the question myself assuming – correctly in most cases (in fact in all cases but one) – that it might offer the opportunity for a good conversation, sometimes indeed a friendship.

I think it is a pity that we should immediately look for the worst possible interpretation of any human contact. That is where we appear to stand now. I no longer ask.

‘I think it is a pity that we should immediately look for the worst possible interpretation of any human contact. That is where we appear to stand now.’

Yes, but it is more than a pity: it is an outright shame. And we know who is doing this, and why.

A fellow Hun! And not just any, but a thoroughly excellent translator. Let me do a quick plug for The Tragedy Of Man (and i must check out your translation!), I think its first English translator was Jewish too? William Loewe.

And Krasznahorkai. Haven’t read him yet and only ever seen Werckmeister Harmonies – i think about that film a lot lately, too prescient of 21st century of “the west” (not the KL likely had that in mind at the time of writing).

My grandparents / parents chose to keep “living adventurously” so they stayed put in ’56 as well. I was quite miffed about that back in the day when i was young and there seemed to be no end to the regime. Now i’m not so sure – living through the horror of communism has given us such robust immunity against today’s all-pervasive marxist/wokery tosh that in retrospect i’m somewhat tempted to admit that it might’ve been a price worth to pay. It was hell though. I’m of the outgoing generation (mid-50s) whose future was completely stolen from us. Glad to see today’s young ones doing fine.

Anyway. Pleased to see a fellow Hun. As for where i am from, Pannonia Prima.

My mother-in-law (an upper-class Englishwoman) once asked my son-inlaw (who carries the name of Singh) where he was from. The reply was ‘Bradford’ which is where he was born and still lives; he never visited the Punjab until he was in his forties. “But where are you really from?” was the follow-up question. Fortunately no offence was intended or taken and both remained good friends until my mother-in-law passed away some while back. Oh, if only we could return to the good old days…

It is remarkable that any Jewish life survives in such an inhospitable environment. I’ve lost count of the casual antisemitic comments that I’ve heard at my very woke and multicultural workplace. It seems to be the glue that binds them all together.

I must be rubbish at this existential angst lark.

Would the question “where are you from?” elicit a heart rending account of my struggle with the fact my Grandfather was part of the evil military/industrial complex that brought us to the carnage of the First World War?

[He was a smith at Armstrong Whitworth in Newcastle]

The answer would actually be two words “Lincoln, why?”

Thank you. I was intending to make a comparable comment — wishing especially to avoid any impression that, because these existential questions don’t trouble me in the slightest, I was proclaiming superiority, or I was implying that Rev Fraser and others should “man up”.

Your words do the job nicely.

Appreciate in some parts of the world (Northern Ireland comes to mind) it might seem a threatening question but generally I always saw it as a conversation opener. It allows follow up questions whether you do or don’t know anything about the place someone comes from. I’m also really interested in other people’s family histories – how they got to where they’re from. Coming from long lines of immigrants on all sides hardly surprising.

Giles, I always look forward to reading your articles, they ooze with such heart-felt expression and honesty.

Dear Giles, about the ‘where are you from’ question.

I do appreciate that this question has caused you disquiet, but here follows just a little personal observation that I hope may offer you some reassurance.

That is to say, that over the years my wife and I (English and, as far as I can judge, of unremarkable appearance) have had our ‘provenance’ quizzed in a variety of ways. This has been both at home and abroad. In England, Italian and Spanish people have insisted that I am – surely? – Italian or Spanish; also ‘Spanish’ in France; ‘German’ in Italy; ‘clearly Turkish’ in Germany; not to mention ‘Do you speak Arabic?’ in Regent’s Park. A chatty Jehovah’s Witness caller absolutely would not let go of the ‘where are you from, I mean really from?’ line of enquiry when my wife answered the door. Apparently, Mrs Bloke was ‘obviously from somewhere in the Mediterranean’, which was news to her.

So, need ‘where are you from’ questions be ‘threatening’, or intended to make you feel you don’t belong? Hardly; could easily be just friendly curiosity or making harmless conversation.

I think it was a reference to Scottish nationalism…?

Yes, quite possibly. If so, perhaps he could have played his Fraser card a little more cannily.

It’s refreshing to have an article on identity with the accent on the personal rather than the political.

We receive some of our personal identity from our forebears. My knowledge of my ancestral identity is limited to my father’s side which was Welsh Methodist/Congregationalist. It’s a background I’m glad to own as a significant part of my heritage.

However the identity I treasure most is that of a child of God. Every human being is a child of God in a general sense in that we are all created by Him. But God wants to be much more than a natural Father to us. Sadly many children grow up not knowing their fathers. Tragically many of God’s natural children today do not know Him in a personal relationship because of their neglect or unbelief.

At the heart of Christianity is the invitation to know and love God and be known and loved by Him in a relationship which is eternal, transcending death. This relationship is made real and experiential through the gift of the Holy Spirit through whom we encounter the Father’s presence and love in our lives. This brings to us a deep and wonderfully positive sense of identity as a beloved child of God in the light of which all other identities are as a candle to the Sun.

I will certainly read his book!

People have tried to stop being Jewish over the centuries and failed because it is so much more than a religion; he speaks of a secular Jew.

I am a Jewish Christian and a lot fell into place when I realised that Christianity is Jewish.

You’re overthinking it. I am the way, the truth and the life and no one comes to the Father except through me. It’s the same choice everyone has had to make for two thousand years. So make it.

It is indeed fortunate that Giles was not elected as Bishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh.

The question “Where are you from” is a question that all of us who are immigrants (or potential immigrants) will be asked in interviews in Scotland

After I had to retire from the Church of Scotland we moved into a flat we had bought in the Presbytery where I had exercised some Episcope. Now I realised that having thumped my brothers and sisters in Christ with my crozier that no one was going to want me sitting in the back of their Churches so i went to the Scottish Episcopal Church which offered my table hospitality. However there was a new rector, fresh arrived from England. On one Sunday he treated the congregation to part of Henry V speech at Agincourt, (which worked well in the context of the sermon). However it was not well received. He looked puzzled and continued.

On the way out I said to him, “The Agincourt reference. You do realise that we were on the other side” I had to actually teach him Scottish Episcopal history, no one had botherd given him an historical induction course.

So I suspect that it was with Giles. Clearly he did not understand that the Scottish Episcopals would ask him that question as it enabled them to anchor themselves.

It is not that the Scottish Episcopal Church is against immigrants, a recent Primus was a fellow countrymen of mine. however it is going to want to make sure that people do know where they are coming from.

I look forward to reading Giles’s book

Here’s a stark statistic. Eighty per cent of all acts of religious discrimination across the globe are against Christians. Contrary to popular belief, Christians are also the most persecuted religious group in the world. Bible Society July 2015

100 million Christians currently face interrogation, arrest, torture or death because of their faith. These are in countries in places as diverse as Asia and the Middle East. There has been a seven-fold increase in persecution globally in the last ten years.

But for tiny enclaves Christianity didn’t take anywhere in the Semitic world. “Judeo-Christian” is a misnomer. Jesus was a Jew, but Paul was thoroughly Hellenized; and Christianity is an Hellenic religion, a “world” religion as opposed to “tribal” cult, based on reason not parochial allegiance. With few exceptions, diaspora western Jews long ago abandoned Judaism (but for its “lodge” type advantages) in favor of the Hellenized, rationalist worldview.

After the Queen’s Coronation, Prince Philip is said to have quipped to her “Where’d you get the hat?” which could be viewed as merely a bit of flippant banter or, alternatively, as a rather more profound reference to her lineage of succession. Either way it seems to me to betoken an easy-going nature of their relationship.

Best thing you’ve written, Giles.

..and the best thing I’ve read on UnHerd.

I remember when I was a child at junior school a classmate innocently confided that his dad referred to my dad as “Old Dutch Disease”. To his credit, my father merely chuckled when I told him later and didn’t explain. Hilariously, Mrs Jones discreetly moved me to the other side of the classroom the following week. Of course, such sectarian silliness isn’t worthy of a mention these days with so much else to concern ourselves with. In any case, 35 years later a policewoman dropped the bombshell that I’m actually Scottish, after all! lol

Extended family story. They were married in the Great Synagogue in London, migrated by ship to Australia, where they immediately became Methodists. I think quite a few people of Jewish background made a similar move. Easier to get by in racist Australia. They are both dead long ago, but none of their children, grandchildren or great grandchildren know the slightest about being Jewish, or being Methodist for that matter.

Genealogy, biology, culture: a person can no more reject his acculturation than his parentage. No one gets to chose. Contingency is a primordial existential structure. Rejection of one’s native heritage is a form of deep suicide. Almost nothing has proved more noxious to Western man than his bourgeois fetish of individualism.

Racist Australia? That comes as a surprise on the basis of what I was told by someone (now about 60) who was brought up in Australia.

It was only in her teens that she learnt from her mother that her father was Jewish. Strangely, she did not know what ‘Jewish’ even meant, and had to have it explained by her mother.

I asked her, hadn’t anyone in Australia ever asked her whether she was of Jewish family, what with her surname being Cohen and all? No, not even once. Her own analysis: people in Australia don’t take an interest in this sort of thing.

I am an Australian who is older than your friend and remember snide remarks being made about Jews when I was young, especially about their wealth. There was talk of “reffos” who arrived with gold they had secreted during the war. Of course, Jews were only one of the targets of racism, which continues to be directed at anyone of Aboriginal, Asian, Middle-Eastern etc appearance or background. Add misogyny and you get a culture in which white men do well. Australian Aboriginal people are “the most incarcerated people in the world.” Aboriginal people make up 3% of the Australian population, but they make up 30% of our prison population. Sadly it is true that many Australians “don’t take an interest in this sort of thing”, and our government likes it that way.

How will we know when we’ve achieved “diversity” if we can’t ask people where they are from?

As a person of English birth but currently resident in Australia, I am picked immediately here as “a Pom”, but when in the UK it is never long before someone politely enquires whether I’m Australian. So I never belong.

I have found recently, however, that people hesitate to ask the ice-breaking question, “Where are you from?” and I can see that it’s because they’re uncomfortable and don’t want to upset me. For me, that’s a definite advance on the previous situation in Australia, where people just didn’t care whether they upset you, sometimes were so gross they didn’t even know they had. And it’s an advance on the previous situation in England, too, where the question would be accompanied by a certain slight intonation that indicated it was a putdown.

So for me, the new hesitancy represents an advance, albeit in a still-unfinished business. People are more aware, more sensitive to the other’s welfare.

I’ve found a way to help things along, too. I now try to make some point or other which will give the game away as to my origins. Then, reading the other person’s impulse to question followed by the curtailing of it, I jump in quickly with a smile and volunteer my origins in a way that works seamlessly into the conversation.

This has worked like a charm, every time. The other person’s body visibly relaxes, then after a slight pause, having being given permission, they ask for more. The curiosity is invariably warm and genuine, their politeness and thoughtfulness has been rewarded with positive feedback, and we then get to know each other better, improving our knowledge of self and other in the process.

Give it a try, if you like. And don’t look back at the past through rose-tinted glasses.