The carnival, before the bad times began. Photo: Oli Scarff/Getty Images

Given the febrile atmosphere created by the Covid pandemic, lockdowns, and the ongoing anti-police Black Lives Matter protests, the cancellation of this year’s Notting Hill Carnival must have been a relief to the police — as well as the residents of West London. The exporting of a specific American argument about police violence has already spilt out on the streets of Britain, so it was likely to be a higher risk event than normal.

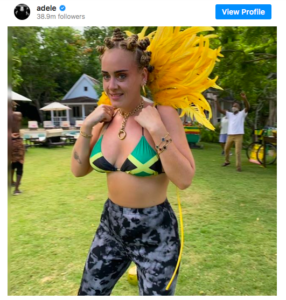

Still this year’s event was not entirely casualty-free, with at least one carnival-related victim — the eight-times platinum selling and multi-award winning Adele.

Poor Adele has already been the subject of mobbing in recent months, having commemorated her 32nd birthday this May by releasing a photo of her looking distinctly slimmer than before.

Perhaps anybody in the public eye who releases photos of their body in the expectation of positive feedback should accept that a portion of the online public is not wholly positive about anything. On this occasion, the attacks came from people who advocate “body positivity” — that is, they argue that people who are overweight should not feel any shame over the fact. (As it turns out, 2020 has not been a good year for the “fat acceptance movement”, with the associated link between severe Covid and obesity.)

Now, barely three months later, Adele put her foot on another of the landmine issues of our time, although a rather more deadly one. From her home in LA, the Tottenham-born singer posted a picture of herself and the heart-warming message: “Happy what would be Notting Hill Carnival my beloved London”. Who could object to something so wholesome and positive? Well, quite a few people as it goes.

It was bad enough that the bikini Adele wore was in the colours of the Jamaican flag, a borderline dangerous act for a non-Jamaican person to risk. Worse still were her Bantu knots, a hair style originating in Africa and worn by women of African descent around the world. It was over this outrageous disrespect that the hordes descended.

“If 2020 couldn’t get any more bizarre,” one award-winning journalist declared, “Adele is giving us Bantu knots and cultural appropriation that nobody asked for. This officially marks all of the top white women in pop as problematic.” A remark that is of course in no way racially problematic.

Other social media users declared that “If you haven’t quite understood cultural appropriation, look at @Adele’s last Instagram post. She should go to jail no parole for this.” Another wrote “Bantu knots are NOT to be worn by white people in any context, period.” Perhaps the most popular response was from Jemele Hill, an American journalist with over a million followers on Twitter who has previously sought notoriety by claiming that the United States is historically almost as bad as Nazi Germany.

It’s hard to read all this vitriol and look at the photo of Adele without pitying her, with that doey, slightly unsure, deeply-hoping-people-will-like-her look in her eyes. Not for the first time we see a person put themselves before the mob and having no idea of the onslaught they are about to endure.

Fortunately, at least on this occasion some prominent figures were willing to come to the rescue — including the new, more sane and reasonable remake of David Lammy. Responding to the hoo-ha, the Tottenham MP said that such “humbug totally misses the spirit of Notting Hill Carnival and the tradition of ‘dress up'”.

To some extent, this is a generational divide. While someone of David Lammy’s age still believes in people’s right to do their hair in any way they want, those raised in a later era do not share this liberating ideal. But perhaps, equally pertinently, the Adele episode reveals the specific importing of American ideas, about culture and race. For as Lammy pointed out, wearing costume and indeed “appropriating” part of the dress and cuisine and even dancing of carnival is part of the point of the Notting Hill event. The tradition has gone on precisely because people of all backgrounds — even William Hague at one point — have wanted to be a part of it.

This particular element had always been part of the point and was never a problem until certain culture warriors in the United States tried to make it so. Indeed there is something ironic about American activists, who know nothing about the Notting Hill Carnival, trying to impose their own cultural norms on a singer from London celebrating a London event, and doing so in the name of opposition to cultural appropriation.

Yet it also provides an opportunity to once again reflect on what these opponents of cultural appropriation are actually urging, that art and literature should be allowed to consist of nothing other than a succession of memoirs, everyone stuck in our own lives, none of us at any point allowed to try to soar out of them.

The same rule goes for every other realm in which the doctrine of “cultural appropriation” is being attempted. It is a world in which people would not be able to play or listen to music across cultures, all of us stuck in our musical silos, forbidden to communicate with each other and forever in our un-evolving cul-de-sacs delineated along carefully-marked racial lines.

If people were not allowed to borrow fashion ideas from other cultures, then we would forever be forced to live in an almost literal straitjacket decided for us by dint of birth and after which we would have no freedom of expression or choice.

Anybody not mentally imprisoned by America’s culture wars would recognise that to live in such a world would not just be boring or limiting but stultifying. I may have no special desire to do my hair in Bantu knots, just as I have no special desire to attend the Notting Hill Carnival or drape myself in flag-designs of any particular nation. But if other people do, then good luck to them. That spirit used to be known as liberalism.

The fact that it now seems so alien to people in the United States who still call themselves liberals should cause the deepest self-questioning about the sort of ideology they have come to inhabit. It is not liberalism, and it is certainly not anti-racism.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeAgain Murray gets to the heart of the matter and does so with efficacy and elegance…

Careful there Matt, ‘elegance’ could be interpreted as England indiscriminately and presumptuously looting from the Italians and the Spanish! For the Hyperboreans, ‘Grim assertion of hard truths’ seems a better way for Northern nations to stay in our own lane. 🙂

Anyone with a grain of intelligence can see the limiting lack of logic of the culture appropriation argument. Should a black man from rural South Africa not be allowed to wear a suit? Should a white woman from South Africa not be allowed to wear beautiful African fabrics (sheshwe) and listen to kwaito music?

If we followed this logic to the letter you would not be allowed to speak Afrikaans. Alternatively the language would have to be purged of any appropriated words and structures which in this particular case meant going back to Dutch. At the same time one could feel sorry for the coloured community as they would be neither here nor there.

Regards,

Yes, it has gotten that crazy. But it started out with a possibly arguable point, albeit firmly embedded in an oppression narrative. That is, it was intended to refer to instances where the dominant culture co-opted the cultural products and heritage of the minority culture, thus preventing them from fully benefiting from the fruits of their creation. An established white writer publishing an indigenous story and profiting from the sales would be an example. The indigenous creator might not be an individual but a community, and their stories were not for sale, but their ‘intellectual property’ has been effectively stolen, just because it was easy to do so. In this case, one might see how damage is done to the less powerful culture, and how they might feel violated. Anyway, there’s a moral argument there and the tricky thing is where to draw the line where violation has actually occurred and where not. Currently, in the mindlessness of the movement, taking offense has knocked down any line that might have existed.

You are 100% wrong. (And a racist.)

There is no theft, there is no damage, there is no violation, BY TELLING A STORY!

This is nothing but BS and gaslighting.

Not by telling it, but by profiting financially by the telling?

Can’t work out the ‘racist’ bit – culturalist, (which is what most ‘racism’ really boils down to) but I doubt it..

That’s an interesting point, but what is the dominant culture in this instance? At my primary school the dominant culture was Irish, even though we were in south London. On St Patrick’s day even pupils who weren’t Irish donned a shamrock. Was this cultural appropriation? Actually it was in large part to avoid getting beaten up. Poor Adele has been beaten up anyway, which just proves that bullies will never be assuaged

The context I am thinking of is Canadian, as that is what I am. The native cultures of Canada, naturally, never had English Common Law. They had no conception of individual rights. Their stories, which constitute their literature, are part of a collective oral tradition and not ‘owned’ by any individual. Thus the concept of intellectual property rights has obvious difficulty trying to map onto their culture.

According to Western tradition, no one ‘owns’ a story. People own the exact form it appears in, be it a song, novel or whatever. That is, there is such a thing as copyright infringement and property rights. I believe a copyright violation would be considered a tort, a form of injustice that I have the right to seek redress from, as any artist can. I can protect myself, my ‘story’, via the law. Now, how does a native culture with an oral tradition protect itself? Just because they don’t happen to have a written tradition, and are now perforce subject to English Common Law, it’s open season on their cultural capital? Perhaps you can see where a grievance might arise. In our terms, they have no case. But as I said, one might see how they could be unhappy, nevertheless. Thus the invention of ‘cultural appropriation’ as a kind of defense, because what else is there? It’s wrong-headed to be sure, but a lot of wrong-headed stuff gets created by people who feel hard done by. Better to try to understand than to simply ridicule the silliest aspects of it. Thanks for asking.

PS. Thanks too for being the Andrew who did not call me a racist.

Hi Alan, I don’t know your country, your comments help to explain why the issue has such resonance there, and I know similar issues arise in Oz and NZ. The situation’s not the same in the UK, but it’s still a bit ironic that many of the commentators who inveigh against the sensitivities you describe display a similar sensitivity when it comes to a perceived threat to their own culture. Pots calling the kettle black? (now pots, they really are racist)

I think this sort of thing raises ethical dilemmas that aren’t easily resolved. On the one hand, there’s a long tradition among humans of the sharing of stories, which enriches other cultures without depriving the originators of access to their own stories. Those originators have probably also benefited from hearing stories from other cultures and weaving them into their own.

On the other hand, now that we have a situation where individuals can monetize the telling of stories and claim ownership of the telling, it does seem unprincipled to capitalize on a people’s folktales and pocket all the proceeds. I’m not sure this is an injustice that can be solved by changing copyright laws, though (it sounds like a legal minefield); maybe the only thing that can be done is to hope that such authors have a conscience and would choose to share the profits with their sources.

It could also be argued that people who collect and record folktales are doing everyone a service by preserving these oral traditions and making them more widely available, thus enhancing our understanding and respect for the originating culture while adding to humanity’s pool of knowledge and sources of inspiration.

You’re totally right that this comes down to ideas around intellectual property. I think it’s relevant that the law don’t give ownership of intellectual property for all time, but only for a limited period, after which it becomes in the public domain. I think this is a recognition that in a certain sense ideas and stories, once they have entered the community, no longer belong to an individual. Not in anything like the same way an object, like a shirt or car, would.

The type of ownership we have created is intended to have an overall positive benefit for individuals, who are able to gain from using their idea or selling it, and to the community, because the creators of the ideas are able to make a living and eep working.

In some ways, the problem of modern individuals claiming the cultural works of others is not dissimilar to the problem of biotech companies claiming the works of nature. Can anyone really claim ownership of such things?

On the other hand, there is nothing to stop members of indigenous communities from using the same stories and knowledge to make money. And it’s not like any of those individuals alive today actually came up with them either.

I’ve wondered though if the idea of intellectual property may have outlived its usefulness. It seems to have become the tool of corporations in order to control the economy, at the same time we get floods of bad products, books, and music – while on the other hand access of the community to use ideas for their benefit can be blocked by those with money.

@unherdlimited-7bc5f2f1017ea56b1bb2d971a6190dbc:disqus you said what a friend of mine with Native American background has said. He has talked with people who sell items like dream catchers made in China and asked them if they know the meaning of them. Also sharing his opinion on buying them from Native Americans. This is peaceful and makes some sense. He does not attack the people or speak harshly, he merely seeks to educate them and he does not choose to do it regarding ridiculous things that make no sense, like music and fabric.

One of the other issues he has mentioned is people wearing fake headdresses. He educates people on the meaning. Honestly though, I suppose the headdress could be likened to a crown. Royalty could be offended every Halloween at children and adults who dress up as kings and queens!

This whole “cultural appropriation” thing has gotten absolutely ridiculous. It’s the, “I can hunt down a way to be offended by anything, just let me look hard enough.” I have no problem with the people from a particular background educating people on the meaning behind a cultural event, hairstyle, item of clothing etc. but going in for an attack, demanding people to have researched the meaning and then not to take on, make or wear or do something from another culture is just finding a way to be offended and miserably frustrated and angry.

Yes. As for the headdresses as analogous to crowns, it depends I think on the significance of the headgear as a cultural marker, its meaning for the people who use it. I think it all boils down to case by case and just being respectful as person in the world, not some stupid rule to use as a political or ideological weapon.

@unherdlimited-7bc5f2f1017ea56b1bb2d971a6190dbc:disqus I would say try a little kindness- don’t assume the worst intentions along with not taking everything so personally.

I agree with you, but logic and Marxism have little to do with each other. What the Marxists are trying to do is manipulate impressions and bring on board as many gullible people as they can. It’s an old trick they’ve been playing and perfecting for decades, and social media has opened up a whole new opportunity for using it.

David Lammy saying something sensible? I almost choked on my Reggae Reggae sauce.

You were not alone!

‘I’ve never heard such humbug in all my life!’

If you want a real example of ‘cultural appropriation’ (which has of course been going on at every level since man stood on his hind legs, and is a natural and organic part of all societal interaction), how about the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra, dressed in dinner jackets and bow ties, playing the ‘Eroica’ symphony; the dress, music, instruments, concert hall rituals, all directly appropriated from European culture. Should we be annoyed at this ‘theft’? Of course not. It is to be celebrated, not denigrated.

Leftists believe the only people who can appropriate other cultures are people of European ancestry. The Left’s insanity / inanity flows in only one direction ….

For that matter, the suit and tie, originated in the West, is appropriated daily by millions all over the world of whose culture such costume traditionally formed no part. Do we care?

As ever, Murray rocks!

By the by, when is Peterson returning to the fray?

JB P has Covid apparently.

But the left calls that ‘colonization’ – the manner of dress are imposed upon others by a dominating culture that then ‘appropriates’ the victim culture’s style when wanted.

Except suits weren’t really imposed on the rest of the world. If that were true then only western colonies would wear suits. The idea just spread.

(Western dress is often driven by US cultural dominance these days of course. Most European style dress has actually disappeared)

What is the difference between “cultural appropriation” and “paying tribute”?

Perhaps this Adele lady, is demonstrating her appreciation of the Jamaican/Bantu culture?

Why do leftists always assume the worst of people?

‘Why do leftists always assume the worst of people?’

Because they themselves are the worst of people. And they assume that everyone else is as unpleasant as they are.

Good point…. 🙂

Actually, an idiotic point. As with everything, there is a spectrum and to identify ‘leftists’ (whatever that term means in this context) being the worst of people is to identify yourself with the worst of the current ‘cancel’ culture.

By the way, I completely agree with the thrust of the article, which is spot on, as usual.

Well put sir.

No Mikey, “leftist” are the worst of people.

🤔no they’re not, yes they are, etc. Facile and in no way enlightening.

I came to UnHerd, as a refreshing alternative to the ‘gender identity,’ ‘politically correct’ nonsense of Liberalism.

Yet here I find as much intolerance as over there.

I agree with everything in this article as an example of some sections of of Liberalism.

But dear people please cannot you disagree without resorting to such undignified assertions?

To gereralise one section of society as “the worst of people,” is uncalled for and unproductive. It does not help at all, only polarises even more.

All lables are simply delusional, especially ‘left’ and ‘right.’

Best wishes to you all

But they are the worst. Controlled by Soros, the DemocratSlaveryParty and Xi.

Now you’re just being silly.

Look mate. You are controlled by the DemocratSlaveryParty in the UK and you know it.

But you have to admit it was funny … [don’t you?]

Because they are the worst of people ……

Another good essay from Douglas Murray. Thank you! As an American, please, I beg you, do not confuse the insanity / inanity of the Left with normal human beings. Since the mid-1960’s, radical Leftists have been infiltrating our universities, Hollywood and the Main-Stream Media. These Lefties are a gaggle of highly-urbanized, totally-dependent, perpetually-outraged people who are mired in envy and hatred. There are a couple hundred million of us who reject their politics and their debauched culture but it’s going to take time to root them out. They’re burrowed in deep like an Arkansas tick …..

Hello Perry.

Deluded they are. Yet to ascertain they are “mired in hatred and envy,” is just not fair. Some probably are, but most of them are just deluded.

Fair enough …..

ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»ðŸ‘ðŸ»

Not being a Twitter user, I find it easy to despair at what is reportedly trending/popular in the Twittersphere. Out of interest I followed the links provided and, to be honest, the vast majority of responses to the original postings were in support of Adele and, more importantly, pointing up the ludicrous nature of the cultural appropriation claims and the crazy hypocrisy expressed. I felt somewhat reassured at the positive nature of the general debate.

After reading your comment and going to take a look … I too was pleasantly surprised at the people telling the outraged Americans that it was they who were out of touch, and telling them off for presuming to be the cultural guardians of cultures they knew little about.

Truly the larger issue is American cultural imperialism!

Yes, lovely isn’t? 🙂

I think my concern is that the original Tweeters see themselves as, and would like to be recognised as, the ‘liberal elite’ – defining what is right and what is wrong for you and me. Or even less pleasing, it’s simply clickbait. Both tweets I delved into were by journalists. One, an ‘Atlantic’ contributor – a solidly liberal, established publication. Anyway, if this truly is the voice of the liberal elite, I’m afraid the liberal elite is proving itself as tin-eared and out of touch as it has done for the last 10 years. Boris and Trump can sit back comfortably and watch the Left eat itself. Again. This isn’t a happy state of affairs for democracy.

Yes and people from Africa often the most stringent critics of the Americans.

Douglas is a sane voice. My only criticism is that in writing this article he is granting a degree of credibility to people and ideas that deserve only to be treated with derision. The concept of cultural appropriation is merely the most stupid discharge from a civilisation that appears to be in a state of terminal collapse.

As with many things, the ‘it’ always goes over the top. I prefer to see it as paying tribute as Stephen says above. If you aren’t making fun of someone, then where is the problem?

I think you have valid point here. In their attempts to be polite and find some common ground, conservatives always seem willing to concede a little something, early in the argument as if trying to gain a degree of acceptance before making the point. ‘If i agree with him on this….perhaps he’ll be more likely to see things my way’. This has been going on so long now that the little concessions have resulted in an accumulation of lost ground, and as you say has given credibility to often ridiculous things.

Willie John Mcbride approach was ” To get the retaliation in first “. What I find amazing is how threatening people have become yet far more brittle and sensitive to pain. On most of the construction sites I have worked people have been frank with each other but there is a lack of spite yet the men were tough and most could fight.

It’s also surely about getting to know another culture and having an experience of it. I’ve lost count of the amount of times we are exhorted by these degenerate liberals to ‘walk a mile in my shoes’ etc… etc… to ‘understand my identity’ etc… and the minute someone does they’re rabidly accused of theft and extortion – if I go to my local curry house and eat a biryani is that cultural appropriation? If I purchase the ingredients and cook it at home for a party, is that cultural appropriation? Lunatics.

“It is not liberalism, and it is certainly not anti-racism.” Nope. It’s neo-Marxism. It’s the oppressed letting us know who’s boss. Or who will be boss as soon as all the oppressors, like Adele, fall in line. Of course, the irony will be, the moment the oppressors do dutifully submit to staying in their lane, they will be attacked for the greater crime of ignoring the sufferings of all the minorities of the world, the way their haughty privilege has allowed them to do since forever. So fight back. Be like Lionel Shriver and wear a sombrero.

Imagine if the Scots got upset every time someone somewhere in the world wore tartan.

Speaking as a Scot who has never, ever worn it, in any form, they can have it. I fact I wish they would buy ours up.

The English have never apologised to the Celts for stealing our Scotch eggs, whiskey, purdie bread, soda bread, tattie scones, full fat bagpipes, deep fried pizza, battered Mars Bars, Welsh rarebit, Lorraine Kelly and Rab C Nesbitt from us, and other priceless treasures! At some point the International Criminal Court are going to have to get involved. We’ve tried being nice but it’s not getting us anywhere..

Like Rod Stewart, the Scotch egg was apparently conceived in London but masquerades as ‘Scotch’.

Sounds like ‘Fake News’ to me. 🙂

Thanks for Scotching the rumour. ; )

Well that’s the first time Lammy has said anything sensible for many years.

Appropriate, appreciate, celebrate and integrate.

Well said. The ‘cultural appropriation’ complaint is profoundly racist – and separatist/apartheid. I am a Paddy who has married one beautiful Hindu woman born in East Africa, (who sadly passed away), and one beautiful Muslim woman born is Saudi Arabia. Is my engagement in these cultures an act of appropriation? No it is engagement! Well done Adele.

Argued the same recently. Good luck to you.

Art & culture is always a mixture of love & theft.

Haha. Like the reference. The great man seems immune to the cultural badgers.

Nothing says culture more than language. Joe Biden’s attempts at fluent English suggest that he is appropriating. I am deeply offended.

Thanks, Douglas. We can always rely on you and a few other journalists to point out this cultural stupidity.

I don’t think she looks good in that get-up – clearly trying to be one of those white girl suck-ups to black culture. But if she wants to look ridiculous, who cares?

American culture just kills everything it touches. And God forbid anyone have any actual fun these days. What a sick country.

She’s British?

I must say she does look idiotic. Who put her up to that?

Yes, perhaps we could all compromise and agree to cancel Adele on the grounds that Bantu Knots look hideously ugly?

Too harsh, she will ‘grow out of it ‘, in more ways than one, eventually.

You know, you have to wonder if all these small-minded people who want to enforce the absurd “cultural appropriation” mantra don’t have anything better to do with their lives. I mean, really. From now on, I think we must insist that people living in sub-Saharan Africa please refrain from wearing Western business suits. It’s offensive to the cultural appropriation crowd. Except… it isn’t.

I went to Saudi Arabia in the early 1980s to help open a new hospital in Riyadh. There were people working there from all over the globe. We appropriated one another’s cultures willingly and openly, both humorously and respectfully. We learned a lot from one another, and we laughed with one another, not at one another.

When we were getting ready to return to the U.S., one of my young Saudi friends suggested that I purchase an authentic set of men’s Arabian formal wear. He took me to a local tailor, and everything was custom-made, or as the British would say, bespoke. I still have my thobe and gutra, along with many embellishments to this day.

I wore the entire regalia to a hospital management meeting when I got home. Everyone loved it. Then, 9/11. Suddenly, if I dared to wear these Arab clothes, people looked at me somewhat askance. But no one ever – especially not any Saudi – ever accused me of the ridiculous non-crime of “cultural appropriation”.

Some people live to be offended. It makes them feel virtuous. I suppose all these easily-offended folks in the UK would like to see T.E. Lawrence’s name and exploits expunged from the history of Great Britain. In which case, along with erasing the names of Winston Churchill and Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, et. al., these little snowflakes would be content to live in their lily-pure ( notice I did not make the grievous error of saying “lily-white” ) culturally-sterile Mediocre Britain.

Bring on real diversity. Celebrate other cultures by appropriating their distinctives. And… grow up.

You miss an important point. When we (westerners) do it, it’s cultural appropriation. When they do it, it’s western cultural imperialism. it’s a lose-lose situation for the west. Fortunately for the west, it’s still mostly all hot air.

Murray is brilliant here. Calling identity politics out as an American ideology is important. That makes criticising it an attack on the powerful not the powerless.

The Adele fiasco is a case in point – the Americans were bleating about the cultural appropriation of Bantu culture. In the twitter thread started by David Lammy however people from the Bantu culture jumped in to point out that they didn’t care and were flattered. Black Americans claiming ownership rights of Bantu culture is like Irish Americans overriding Irish people’s ownership of Irish culture.

To realise the true extent of the damage that our complete over consumption of American culture particularly over the last 10-15 years has done you have to have lived in America and come back to England recently. It really is quite revolting and explains our utter inability to stand up for ourselves and to constantly go along with this belief that everything else (American anything) is better and I think is what drives younger people’s distain for this country due to the conginitive dissonance caused by living in this cultural American world online and on Netflix etc but being physically in England and all the differences that brings this then causes this anger.

Actually, having recently been exposed to the views (on YouTube) of many Americans now living in the UK about their lives here and living in the UK in general, I’m pretty sure we’ve got the better deal. I like the US and most Americans I’ve met, but I don’t idolise it or them.

Surely the Carnival is Cultural appropriation itself, since its roots are in South America, not Africa.

The roots of Carnival were in Europe and taken out by colonialists. They spring from the idea of, for a few hours, letting the devil have its due. In Trinidad, in particular, the slaves and freed slaves aped the behaviour of there masters who, for a day or so, would let them get away from it. It was, however, deeply political and colonial governments tried (and failed) to stop it.

I don’t see this as a left-right or liberal-conservative issue. Rather, a certain percentage of the population of any country enjoys mobbing for the social cohesion and anger outlet it provides them as alienated individuals. There is a totalitarian-minded left and right, who will look for victims to mob because it feels good.

This is not new, only the excuses for it, the names of the victims and the anonymity of the internet are new. The same mentality led to Abbie Hoffman’s “Revolution for the Hell of It” decades ago, and attracts people today who occupy Wall Street, parade for and against white supremacy, join Extinction Rebellion, BLM protests or Antifa in order to have a superficially moral excuse to be violent, either in person or on the internet, etc. The cause matters less than the joy of visible rebellion and attacking a human target in a mob.

Didn’t the Red Guards start off like this?

JF

I’m a big fan of Douglas Murray, but come on, let’s stop blaming America for everything. The UK has plenty of homegrown problems without pointing the finger overseas. Examples: London is a surveillance city that resembles Beijing China and is plagued by knife violence despite ever-increasing bans on everything, you have speed cameras everywhere, free speech is nothing but a memory (just ask Katie Hopkins), industrial output is devastated, you can be jailed for hurting someone’s feelings, and your politicians treat you like you’re all idiot children who must be controlled. It’s truly sad watching the UK become a totalitarian society and no one seems to be putting up much of a fight.

Also keep in mind the United States is a very large and very diverse place. There really is no typical American. Attitudes in New York City are as different from those in the south as England is different from Romania. Unfortunately our news and entertainment media companies are all based in NY City or Los Angeles, California which are both consumed by Marxists and what they broadcast is often out of step with the rest of the nation. We do resist it but they own the microphones.

As for Adele, many Americans have never even heard of her, and those who have probably only remember that one big hit she had a decade ago. We don’t hate her, we’ve just moved on. Only people with too much time on their hands care about her hair.

Much love from the US, but please get off your knees and restore your freedom! We’re busy over here trying to protect ours.

He didn’t blame America for everything but is blaming US centred ideologies for the specific thing he is talking about.

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness.”[Possibly Oscar Wilde.]

I’ve always harboured a particular grievance for Louis Armstrong and his outrageous cultural appropriation of European classical music’s trumpet. It officially marks all the top black men in jazz problematic.

You may think you joke, but for a little while I have been wondering how long it will be before the big band jazz of Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Stan Kenton or the like will be condemned by the cultural warriors for its “whiteness”.

Recently one of the higher ed outlets was bemoaning the reduction in Jazz scholarships, stating jazz was becoming a ‘subject’ only for rich whites to study (and play?). https://www.york.cuny.edu/a…

“As far as I’m concerned, what he did in those days”and they were hard days, in 1937″made it possible for Negroes to have their chance in baseball and other fields.”

“Lionel Hampton on Benny Goodman

Are people of African background culturally appropriating if they straighten their hair? Are non whites culturally appropriating when they die their hair blonde? As a white person should I be offended? In the current climate I should be but I am not because I like creativity.

Nelson Joannette from Canada the most politically correct insane country in the world

Wonderful except for one thing: Most of us Americans do not consider the idiotic ideas that you rightly pillory to be remotely “American”. Call them something else, such as “damaged spawn of multiclturalism and critical theory”.

I think that they meant recent killings in the USA have caused a reaction here that is as if our cops regularly shoot suspects.

I wonder if Adele has any Celtic blood? 5600 years has elapsed since it was first reported recognised now? that they wore their hair in knots. Romans reported Celts with hair like snakes.

So. Bantu or Celt or both. Either way somebody please stop this nonsense regarding appropriation. And as for flags. Plenty of our darker siblings carry ancient British regimental patches on their sleeves and march behind a flag that their grandparents might well have spat on.

Calling that appropriation in the circumstances described, would be non inclusive at least and racist at worst. But it would continue the misintegration if that’s a word, that many seem to want.

I guess I am disappointed. As far as I can tell, I am the only one in this forum who has attempted to describe and represent the idea of ‘cultural appropriation’ from the point of view of a culture actually expressing that grievance. That is, to not simply ridicule, which is easy and which I had already done, but to actually think about where it comes from in real world terms, what is the case being made. I didn’t go too deeply into the example, and was asked to expand on it by another member, which I did. This was good, the way it should be. On the other hand, for my initial effort, someone thought to accuse me of gaslighting, to yell at me using all caps and to call me a racist rather than contend with the case or the argument. That’s fine, one disagreeable poster is easy to ignore, but less fine for the forum’s general health, in my view, is that this uncivil attack got fairly significant upvote approval. Upvotes represent agreement. What were all those upvotes agreeing with? The poster’s opposition to the concept of cultural appropriation, or that it’s acceptable to throw around unsubstantiated accusations and derogatory epithets? I don’t want to think it was the latter, but maybe in some cases it was. Generally, this site has thoughtful articles by thoughtful writers, and a lively comments section, which i appreciate. My wish is that the comments could be a little more thoughtful. Start with thinking about what you ‘like’. It might not always be what you actually do like. Thanks for your time.

The responses to you were less than polite. I also think the “you’re the real racist” is a bad argument.

So let me explain to you why you are wrong. Even if cultural appropriation is a thing, it is clearly a form of American imperialism for American blacks to claim ownership of Bantu culture, and furthermore it’s American imperialism to attack a Londoner for celebrating a festival where people of all races have dressed up like this for decades. People in the US have no say in this.

Thanks, and interesting. Not exactly sure how that makes me wrong though, except that perhaps what I was discussing was beside the point. Could well be. Cheers.

Alan. Don’t let the b*stards grind you down. I for one thoroughly enjoy your articulate and nuanced posts, even when I disagree with your point of view as in this case on cultural appropriation. Please keep on posting.

Thanks!

Cultures have always “appropriated” from other cultures and, indeed, would otherwise stagnate. This would not have been at all a controversial point of view until the coming of Twitter, a toxic medium seemingly inhabited by legions of airheads, idiots and malignants. It is baffling that anyone of even the meanest intelligence should engage with it. The likes of Adele, J K Rowling and others who have become the victims of a twittermob must accept that it is not a good idea to post images or ideas there and expect a sane, reasoned or adult response.

Not too many these days would answer your takeaway question with ‘you won’t catch me eating that foreign muck’.

But if it’s cultural appropriation then we’d be as well just eating what our great grand parents of whatever origin, did. Now look at what the Wokeys have done for me. NO MORE CURRY.

Claiming cultural appropriation is an attention-seeking sheep-bleat expressed by people who have not confronted or acknowledged their feelings of inadequacy.

I understand that many of the beautiful African fabric designs originated in Indonesia and got to Africa via the Dutch.

The whole idea of transgender movement is gender appropriation. No one would dare tell a black or Asian woman she cannot dye her hair blonde, or straighten her hair in a way that matches European hair.. But if a white person sports a non-Euro hairstyle, that’s improper. Which is the exact same thing virulent racists in past eras argued.

Are immigrants to US from Africa supposed to only ever wear native garments in the US???? Now that’s racist!!!!!

imitation is the sincerest form of flattery…

‘Fat positivity’ reminds me of the white supremacist sophistry from Spencer, Duke and other silly people like that. Instead of ‘I’m not white supremacist, I’m pro white!’ it’s ‘I’m not fat supremacist, I’m fat positive!’ Ironically, they don’t come across as very ‘positive’ with their constant bitter Trottist aesthetic…

While someone of David Lammy’s age still believes in people’s right to do their hair in any way they want

Does he? Would Lammy be so indulgent if Adele hadn’t done it just for Notting Hill Carnival?

And if she hadn’t been brought up in Tottenham, where she was supposedly deeply immersed in black culture (which somehow makes it all right)?

Imagine if, say, Kate Moss had adopted that hairstyle and bikini combo.

Nice image. Cheers.ðŸ˜

When I lived in the ME, I sometimes wore a thobe, ghutra and egal. Far from criticism; my local friends applauded.

LOL I thought you were making those words up but no. Thank you! Now I know what a “thobe” is. Do you know what a “thneed” is?

I wonder why the cultural appropriation herd never considers the harm they are doing to those living in poverty, relying for basic needs on the sale of various culturally oriented products.

Do we know for certain that Bantu knots are a uniquely African tradition? Surely pre-roman Britons must have experimented with tying knots across the entire head at some point. The winters were long, cold and boring between planting and harvest after all. I have a hard time believing only one culture on earth ever thought of that.

Human development has always been based on the coming together of peoples genetically and culturally.

I see this got politicized… so I’ll add the disclaimer that I’m what you would call a leftist. Here the right prefer segregation so they would never be guilty of cultural appropriation.

Another Douglas Murray storm in a teacup. He quotes two people who I doubt if many will have heard of to quote two people (on un-named and one famed only on twitter) to report on “outrage”. The sight of him, no doubt through gritted teeth praising David Lammy really doesn’t outweigh the absurd hyperbole of his piece 3/10 do try to find something more important for you to try and save us all from

I think he’s trying to save us from the current Incarnation and scourge of Marxism, which is no small thing. Cultural appropriation has obviously silly manifestations, but it is rooted in the simplistic oppressor oppressed narrative that is the hallmark of Woke mentality. Such pushback is vital.

Where are all these marxists you seem to be scared of?

Burning down various cities in the US.

I don’t think that black people in the US need to read Marx to discover that police custody is not the safest place to be

Resisting police is not the safest thing to do. I think that’s more accurate given the liberal protections that suspects enjoy. Not that I necessarily think such protection is wrong.

Possibly staring at you from your mirror Rick.

I guess you’re not really paying attention. BLM is an avowed Marxist organization very successfully playing the public for political ends. That is easy to verify, just go to their website, they’ll tell you all about it.

Infiltrating most of the establishment over decades. Read “The Long March Through the Institutions” by Marc Sidwell

Authoritarianism, no matter under what guise it parades around in, should be exposed and opposed. If for no other reason than that it easily influences the easily-influenced, which includes the young. The camel’s nose should always be removed from under the tent. The earlier the better. “Cultural appropriation” defined as a moral failing is a form of superstition.