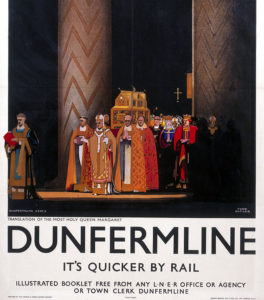

A London North Eastern Railway promotional poster of Dunfermline Abbey. Credit: SSPL/Getty Images

Back in the mid-90s, somebody or other produced a list of the 10 most boring towns in Scotland, which was duly picked up by the papers. I don’t remember which bleak pile of bricks came first, but I do remember the perverse pride I felt upon learning that my hometown of Dunfermline had placed fifth. That seemed a more profound manifestation of dullness than landing the #1 spot would have been; to “win” would mean appearing exceptional, and thus, paradoxically, at least slightly interesting.

That feeble fifth-place ranking captured the depressing atmosphere of weary run-down rubbishness in which we who lived in the “Auld Grey Toun” were marinaded. Our local bookshop and cinema had closed down by that point, so there was not a lot in the way of culture or entertainment, although — to be fair — we did get the panto every year and I once saw Fife’s premier Frank Zappa tribute act, Frank McZappa, play in a pub. Speaking of pubs, we had no shortage of those, and we were also lucky enough to have a swimming pool, bingo hall and some ruins. You might say it was a bit like Waiting for Godot, only we’d all long since given up waiting.

Not that long ago, I would have ridiculed the very notion that Dunfermline contained any mysteries worth bothering about. My teachers did at least try to instill some civic pride: as a child I was taught that my hometown was Scotland’s “ancient capital”; that in the 11th century an important king named Malcolm Canmore built a tower there; that his wife Margaret became a famous saint; and that Robert the Bruce, the last Scottish king to defeat the English in battle, was buried in the Abbey. After that, nothing much seemed to happen for 500 years, until Andrew Carnegie was born. But he had to leave Dunfermline to become successful: a fact that was not lost upon any of us.

That’s a decent amount of history for a small town that nobody visits. And later, I learned more: Charles I, later to attain some notoriety, was born in Dunfermline’s royal palace; and Robert Henryson, a major medieval poet, had been headmaster at the high school.

And yet even to a child it was obvious that Dunfermline was centuries past its prime. Malcolm’s Tower (the “dun” in Dunfermline) was a circle of old bricks in on top of a hill frequented by nobody. The Abbey nave had fallen into disuse after a new bit was added in the 19th century, while all that remained of the royal palace was a wall — which was a great backdrop for staging mock-World War II battles, until Historic Scotland put a gate on it and started, rather too optimistically, charging for entry.

Saddest of all was Saint Margaret’s Cave, a once-sacred grotto, which was accessed through a shed in the car park behind The City Hotel, and which was closed for much of the year (the shed’s design drew heavily upon the “public toilet” school of architecture.) I was told by a guide that the city council had almost filled in the cave completely when they were putting in the car park, but a grassroots campaign had prevented that outrage. Thus even our history seemed a bit rubbish; the town was a place where people did things that were forgotten, or left to achieve greater fame elsewhere. I turned my back on Dunfermline in favour of Moscow, and then Texas, and for a long time I thought that seeing family was the only possible reason for visiting the place.

But my attitude began to change the first time I brought my children to visit. Little Texans, they were growing up under a bright, limitless blue sky; I took them at Christmas, with the benefit that they would see the town as I remembered it, with horizontal rain and mid-afternoon darkness. One day I took them to visit Robert the Bruce’s tomb in the Abbey. The guide was telling the same story I had first heard 35 years earlier, when suddenly he mentioned, as an aside, that there were six other kings buried in the Abbey grounds, but nobody knew which one was which: “We know where they are, we just don’t know who they are.” Having travelled fairly widely in post-communist Europe and Asia, I had seen many identities assembled on less evidence than that. Yet here was Scotland: a country with a nationalist government sitting just across the bridge from this pile of kingly bones — and neither they nor anybody else seemed to care.

I was impressed by this grand an act of forgetting — this sustained, centuries-long indifference. We’d even managed to lose Robert the Bruce — that most legendary of warriors — for hundreds of years: his tomb was accidentally rediscovered in the early 19th century. And our kings, I later learned, were not the only things that we had mislaid.

When next I returned, I spent a couple of mornings in the local library, reading old books on the history of Dunfermline. It turned out that the Auld Grey Toun had been a major site of pilgrimage for centuries, a place of holiness and miracles. Visitors had come from far and wide to venerate the relics of Saint Margaret. One of those relics was her head, which remained on Earth long after her soul had departed for its eternal reward. It was a fixture at the Abbey right up until the Reformation, at which point concerned Catholics spirited it away — first to Edinburgh, and then to the continent — so that it could escape the orgy of iconoclasm taking place in Scotland. The plan worked, and Saint Margaret’s head survived for a further two centuries, before disappearing in a different orgy of iconoclasm: the French Revolution.

It was also around this time that I picked up a copy of the Arden edition of Macbeth, and, reading the notes, realised that the “Malcolm” who kills Macbeth in Shakespeare’s drama was the same Malcolm who married Saint Margaret and built the very tower that put the “dun” in Dunfermline. You’d think my English teacher might have mentioned this, but she didn’t because — I am sure — she did not know. It was as if Dunfermline, secretly interesting after all, was clouding the minds of those who inhabited it, sustaining a miasma of boredom to prevent anyone from looking too closely. How could a place that had once been so rich in mystery, and a sense of the numinous, now be so bereft of it? Our capacity for forgetting awed me. It still does.

This time last year I was home again, and decided to follow the Tower Burn into town, a route that many have trod and re-trod over the centuries. Its banks were overgrown with nettles and the section closest to Saint Margaret’s shed (which was closed) was strewn with litter and serving as the last resting place of an errant shopping trolley. From there, I walked through the car park and on to the Glen, where I paid a visit to Malcolm’s Tower. A bit of the ancient tower had fallen off and lay on the ground amid crisp packets and beer cans. Not too far away, Abbot House — a medieval building containing a contemporary mural by the celebrated writer-artist Alasdair Gray — was also boarded up.

I was heading for the Abbey when, all of a sudden, I spotted a numpty with a hurdy-gurdy standing at the entrance. Intrigued, I lingered a few minutes, and the next moment I saw Gordon Brown leaving the building in the company of some people who I assumed were local dignitaries; I think the Earl of Elgin may have been among them. They were celebrating the opening of ‘The Fife Pilgrim Way’, a new walking route that, it was hoped, would lure tourists over the bridge from Edinburgh into Fife so we could extract some money from them while they drank deep of our sacred history. That’ll be the history surrounded by nettles and beer cans, then? My cynicism was so profound that I could feel a “Disgusted of Texas” email to the Dunfermline Press coming on.

But when I got back to the States, the business of life swept me away and it was weeks before I remembered that I was going to write that letter. And now, a year later, I wonder: what if this level of disregard for the past is, well, typical? What if Dunfermline is just a particularly pronounced exemplar of our natural state? I remember visiting Konye-Urgench in Central Asia, where a kid was grazing a goat outside the ruins of an ancient fortress that clearly meant nothing to him; and also VDNKh, the giant Stalinist exhibition centre in Moscow, where shoppers browsed for washing machines and fridges, indifferent to the monumental totalitarian architecture that housed them. I think about the epic of Gilgamesh, which disappeared beneath the sands of Iraq for so long. The heritage industry exists to serve visitors who are disconnected from the history they stare at. Locals, well — they forget.

Even so, all those forgotten things lie heavy upon Dunfermline and everyone in it. The glory of the town is not so much its past but its status as a mysterious monument to aging — to decay, loss and death. It reminds us that glory days once gone do not come back; that you don’t need to be so dramatic as to decline and fall: sometimes to decline is enough. That which is interesting is not visible, and that which is visible is not that interesting. But if you stare long and hard at the town, it will begin to reveal its secrets. It only took 40 years or so for them to start opening up to me, and as the years pass, I find that the heavy gravity of the Auld Grey Toun exerts an ever-stronger pull upon me. Each time I return it is as if I am edging my way ever closer to some central enigma of existence.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeYou seem shocked by the vandalism of your ancestors, but in truth the 16th century Scotch Reformation was one of the most architecturally destructive in European history.

Whereas in England only two Cathedrals were ‘lost’ in this period nearly everyone of Scotland’s thirteen were unroofed and trashed. The most important loss being St Andrews, the seat of the Primate of Scotland and the only Cathedral that could bear comparison with most of those in England.

Additionally all of the great Abbeys suffered the same fate including perhaps the greatest, Dunfermline, as you so eruditely describe. Thus Scotland has very few extant Royal tombs, unlike the plethora that still exist in England. If it is any consolation things were even worse in Ireland and perhaps also Wales.

Please don’t encourage them. Those are not just kings of Scotland but of these British Isles, rightfully a source of shared affection, just like the kings of Wales and of the Heptarchy ought to be.

These were Scots Kings, who ruled before the Union of the Crowns in 1606

A bloke from Dunfermline told me that as a young man he had always gone up the road to Jackie Os night club in Kirkcaldy, because “there was a better class of woman”. A rather damming indictment I thought.

Night Magic was the club in Dunfermline if I remember correctly but I think buses from all over Scotland used to go to the improbably named Jackie O’s so I’m fairly sure it would have been hoaching.

Wonderful article – thank you. I was born and now live back in Sydney Nova Scotia (New Scotland) and have had the same experience with our history. No appreciation of it when I was younger, but over the decades have realized it is actually quite interesting (considering North America’s short history – it would be nothing by Scottish or European history standards)

`The King sits in Dunfermline town, drinking the blood-red wine`

Surely one of the greatest opening lines in poetry.

I moved from England to Dunfermline for five years in the early 2000s. I thought the town and its history fascinating and was surprised that so little was made of its tourism potential. I too was disappointed by the rubbish along what should be an enchanting walk along the burn.

Frank McZappa was an amazing wee outfit. Oh and it’s the yoonatic lot that need a wee hand up now. Yes, the sad fact is that it’s the union and the wars they so love that is our history now. A casual reference to Bruce’s spider will draw a blank look from the under 40s. Oh and Dunfermline wimin rock. Great article.