No wonder she can't pay attention. Credit: KIRSTY WIGGLESWORTH/AFP via Getty Images

The best way to learn what someone really believes is to watch what they teach their children. For every ten middle-class families who pay lip service to the idea that manners are an outdated, classist construct, nine will still teach their children to use a knife and fork and say ‘Thank you for having me’.

What can we infer, then, from the general state of illustrated children’s books? One thing is clear: we do not value beauty.

Many illustrations aimed at children seem calculated to insult their readership. Flat, clashing colours combine with distorted outlines of humans and animals that convey contempt for their subjects. It is as though we react to a young child’s natural wonder at the world by seeking to present him or her not with wonderful things but instead with foot-shuffling embarrassment and a desire to make off-colour jokes.

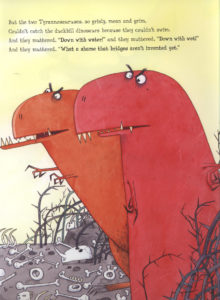

Nothing about Tyrannosaurus Drip makes sense

Take, for example, the story and illustrations in Tyrannosaurus Drip. In narrative terms, nothing about this book makes sense within the frame of reference you would expect a normal three- to six-year-old to have. Meanwhile the illustrations are ugly and unpleasant. The whole work has a strangely arch tone, as if talking over a child’s head at a knowing, cynical adult.

In the Maisy Mouse series, flowers are to be counted, not wondered at

Elsewhere, the Maisy Mouse books combine clashing colours with a strange lack of gentleness or movement in the pictures themselves. The stories at least provide narratives familiar to small children, about experiences most children will have in the modern world. But the series overall leaves me with the sense of a humdrum world, unleavened by dreams, mystery or surprise, where flowers are less a source of wonder than a set of objects to be counted.

Behold the horrible, scrawling illustrations of Unicorn Expert

For an even uglier and less veiled instance of the children’s literature genre devoted to stripping the world of magic, try Sophie Johnson, Unicorn Expert. In this unutterably sad story, a little girl is so consumed by self-absorption and a determination to force everyone and everything around her to be a ‘unicorn’ that she fails to notice when a real unicorn appears in her life.

This never changes, and at the end of the book Sophie is congratulating herself on her expertise in caring for unicorns even as the real unicorn packs its little rainbow suitcase and leaves again. There is no redemption. In the world of Sophie Johnson, enchantment is real but even children are so intent on compelling the world to conform to their ideas that they look straight past it. Eventually enchantment gives up and leaves.

This story, complete with scrawling illustrations reminiscent of a magazine cartoonist, is presented not as tragedy for adults but as an amusing story for chidren. Imagine teaching your innocent, imaginative, open-minded under-five that it is funny to let wonder and mystery vanish from the world.

This matters to you, the adult. Children enjoy (oh so very many!) repeated readings of their favourite books. So a book with eyeball-searingly ugly illustrations, an incoherent story or bad prose that would be mildly irritating on the first reading will drive you to fury by the hundredth.

In some three years of regular library visits, I have learned that attractive illustrations are a crude but effective indicator of an overall higher-quality bedtime story. If you are fussy about good writing, scanning the library for books with attractive illustrations is a useful way of saving yourself from spending the next fortnight purple with Pooterish rage every bedtime.

But beauty in children’s books has a more profound role than simply keeping parents sane. It is central to the moral values we inculcate in our children, at the very beginning of their education. Since Pythagoras, it has been understood that beauty, whether visual or narrative, is intertwined with the good. Sir Philip Sidney wrote in 1595 that poetry (by which, in the modern sense, he means fiction) has a moral purpose: to ‘delight and teach’. That is, it aims both to give pleasure and also to convey narratives that help to shape the moral universe.

Sidney was right. Humans are wired by evolution for storytelling, and we make sense of the world not primarily via facts, but narrative. For a pre-literate child, a book’s narrative and its illustrations are part of a single whole. Thus the pictures we show, in the books we present to our children, are as much part of our children’s education — both factual and moral — as the stories.

And beauty matters. In every culture across the world, throughout human history, we have decorated our belongings and environments and found pleasure in beauty. Though beauty may come in different forms, it is something for which humans feel a profound longing. Scientists have recently argued that this longing extends beyond humans into animal species such as birds and even into larger ecological systems. Telling children cynical or incoherent stories, and accompanying those stories with ugly pictures, amounts to training them to disregard their instinctive longing for beauty, and to sneer at or objectify the world instead.

You do not have to read Sidney, Pythagoras or Aristotle to feel instinctively that showing children beautiful pictures is better than showing them ugly ones. To any parent of a preschooler who cares about this, there are plenty of heartening classics, both vintage and modern.

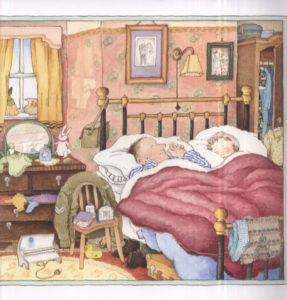

Peepo! is the kind of beautiful classic kids should be read

Sybille von Olfers’ 1906 Root Children offers minutely observed drawings of the natural world, not to mention an exquisite age-appropriate introduction to the Art Deco style. The intricate worlds drawn by Janet and Allen Ahlberg repay close study even by an adult, whether in the playful Each Peach Pear Plum or the beautiful and nostalgic Peepo!

Anna Currey is a contemporary children’s author who gets it right

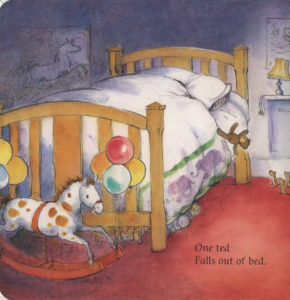

More recently, anything illustrated by Anna Currey’s delicate pen-and-ink and watercolour work (we have and love One Ted Falls Out Of Bed and Rosie’s Hat) will survive repeated readings without losing their warmth and sense of detail.

Why can’t all children’s books look like The Storm Whale?

Another favourite contemporary writer and illustrator in our house is the wonderful Benji Davies, whose modern classic The Storm Whale is both emotionally subtle and beautifully imagined, with something new to discover on every read.

The work of Benji Davies is also genuinely beautiful

Nor do nonfiction titles need to be free from wonder or beauty. Ella Bailey’s One Day On Our Blue Planet series adopts a clean-lined graphic style that is contemporary, spare and still full of life. She guides readers through different habitats — the Antarctic, the South American jungle and the African savannah — giving a glimpse of the wildlife there with just enough narrative to delight parents as well as children. (After two months of requesting the South American one at bedtime every night, my three-year-old can now name some ten species of rainforest monkey.)

It should be clear by now that I do not understand beauty to mean a single style or some dreary notion of realism. Beauty comes in many forms. With regard to children’s books, it is less about the style than a sense that the artist has taken care to represent their subject faithfully and with affection.

This is profoundly important. The default setting of small children is imaginatively ‘being’ something other than themselves: a cat, a fairy, the latest Disney princess. It is a process of exploring and gaining understanding both of self and of environment and is critical to normal social and emotional development. Stories and pictures whose illustrations encourage imaginative empathy and respect for their subject matter will encourage this developmental stage.

Caricatures, on the other hand, by distorting their subject matter in a way that diminishes its dignity, beauty or appeal, have the opposite effect. One cannot easily be ironic and imaginative at the same time, except perhaps in the form of satire.

My daughter often adopts a persona from a story or TV show she has seen, and can ‘be’ that persona for days at a time. But I have never seen her ‘be’ a character who was presented as caricature. Why would anyone wish to inhabit imaginatively a persona who was presented with a sneer?

A young child whose ordinary imaginative play was satirical in character would come across as disturbed to say the least. And how is a child accustomed to caricatures of the world supposed to develop into an adult filled with empathy for others and a love of beautiful surroundings?

Is this ugliness really what we want for the next generation?

Ugly stories with ugly pictures communicate materiality without wonder, conflict without resolution, sneering without kindness, and nonsense without clarification. Such stories train a child to accept those values in his or her adult life, without hope for anything better. Is that really what we want for the next generation?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeMary Harrington nails it. This article is a keeper – pass it on. If you have young minds among you this holiday season, give some thought to the ideas and stories that were presented before you as a child. Real quality speaks to you.