Credit: Getty

When Ahmad Abu Artema was a child, his parents separated and his mother ended up living just over the Egyptian border with Gaza. Seeing fences that stopped him from visiting her house just a few hundred yards away, he wondered why human beings were kept apart in such ways. Earlier this year, now a journalist in his thirties trapped along with 2 million others in the tiny Palestinian enclave, he stood by the border with Israel and watched a bird fly over the barbed wire. “I asked myself why I couldn’t be like that bird, free,” he said.

So he fired off an impassioned, almost poetic, post on Facebook. “What would happen if 200,000 peaceful protesters broke through the barbed wire,” he asked, imagining if they all “raised the Palestinian flag and pitched tents a few kilometres into our own occupied territory.” He signed off with #GreatReturnMarch, a slogan that soon went viral. From this seed, planted online in January, sprouted the border camps and weekly demonstrations against the Israeli siege that have left more than one hundred dead, thousands wounded and now sparked a United Nations war crime inquiry into Jerusalem’s reaction.

Abu Artema sparked a mass movement with one post. He and his friends talked of civil rights and Gandhi – although their cause was rapidly taken over by Hamas, which has controlled the tiny Gaza strip since winning elections 11 years ago, and other militant groups. Their leaders talk also of peaceful protest – although one indicated to me that if the international community failed to respond to their campaign, they might revert to more violent resistance. As I watched this grim theatre of tragedy last week – with tear gas and burning tyres, slingshots and snipers – I heard the crowd chant for rocket strikes on Tel Aviv after Ismail Haniyeh, the Hamas boss, urged them forward.

The frustration and grinding boredom behind that Facebook post are felt often on this tiny slice of land, less than eight miles wide from its border to its sewage–infested sea. Citizens suffer constant power cuts, a crushing lack of jobs, a decaying economy and dismal public services. Escape depends on the whims of politicians in Cairo and Jerusalem – unless you have $2,000 to bribe your way over the Egyptian border when it is closed. Meanwhile, the future looks grim with peace hopes extinguished by hardline leaders – and now a United States president has managed to make matters even worse by formally recognising Jerusalem as Israel’s capital to appease fanatical domestic evangelicals.

Few in Gaza dare criticise their rulers openly. Hamas has slaughtered members of rival factions, carried out suicide attacks and routinely tortured dissidents. One man, beaten and hung from his arms by security officials in the past, asked me desperately how they could ever shake off their shackles? Yet while there, I met also another person who is harnessing the power of the internet to openly defy Hamas, even organising a protest against power failures that got 50,000 people out on the streets in Jabalia refugee camp.

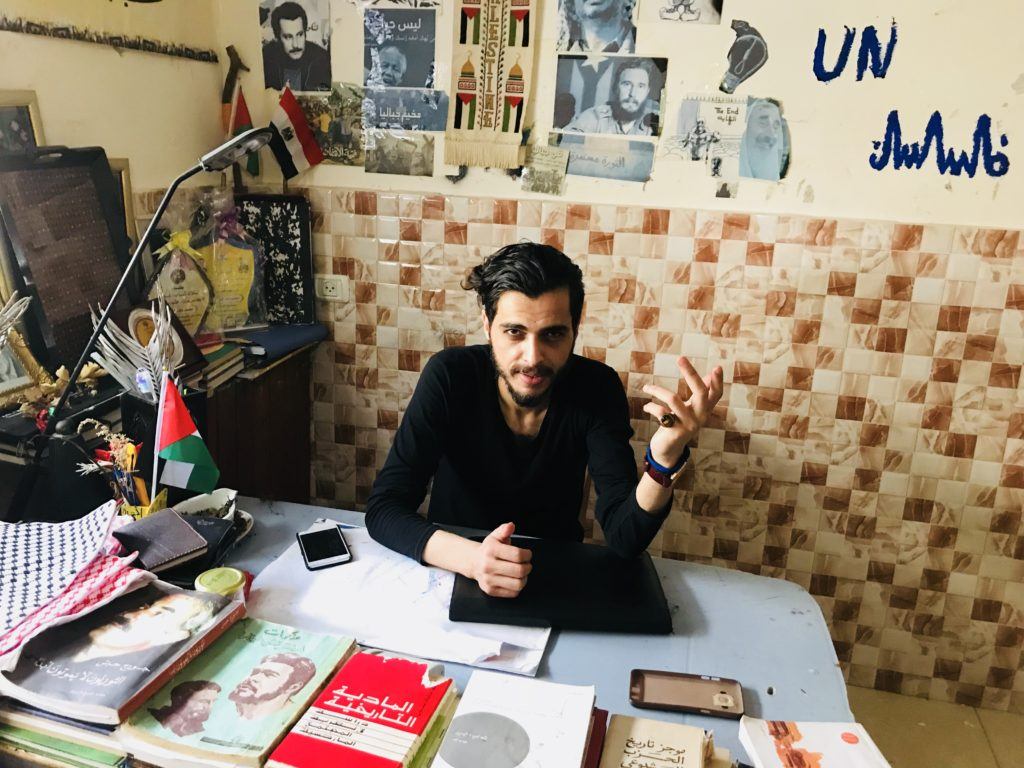

His name is Mohammed al-Taluli. A wiry 26-year-old, he smiles when he tells me about having his long hair shaved off during one of his seven prison spells since the start of last year, and how Hamas goons took all his 1,000 books in a raid on his home, apart from a single work by the leader of Muslim Brotherhood. On the walls of his study are pictures of Che Guevara and Yasser Arafat, while the clenched fist symbol of his Mustamirah movement is painted on the wall outside his house.

“I am an ordinary guy, a Muslim by instinct and a Palestinian by identity,” he said. “My problem is I disagree with Hamas – they have failed in their running of Gaza. There is an absence of basic human rights: education, electricity, travel, freedom of speech. They suppress all those who disagree and that is not why we elected Hamas.”

This is brave talk. Yet al-Taluli, backed by friends, believes strength come from his online presence despite Hamas’ efforts at censorship. His original Facebook account had 80,000 followers before it was shut down, since when two others have been closed. He is already operating another secret account with 1,400 followers who help spread his message – and planning a second march that is seeking to get a quarter of a million people out in support.

He claims Hamas wants people to starve so they lack strength to rebel against its rule, saying the majority of people in Gaza are fed up with dismal caged lives. When I ask al-Taluli what he wants, his reply is simple. “We want democracy. No one should impose religion on others – if you want to go to the mosque, that’s fine. If you want to go to church, that’s fine too. We want the freedom to be creative, freedom from foreign ideologies.” He then wrote me a signed note pledging that Mustamirah “will save youths and provide them with natural life and free expression from a dangerous organisation”.

Like everyone else I met in Gaza, he talks of peaceful struggle. Yet he is opposed to the Great Return March protests since “I can’t endure to see another drop of blood spilled”. One video he posted on YouTube accused Hamas of “pushing the youths to death to stay in power”, which led to one of his arrests. When I ask about Israel, he said: “All of us want the right of return but we don’t want to remove the Israelis.” This nuanced response echoed others I heard, even from families of those who died in protest, although it is perhaps significant that al-Taluli has also had surgery in a Tel Aviv hospital.

This digitally-inspired dissident offered a timely reminder of the internet’s importance. Much of that early idealism about the technology revolution has dissipated with disturbing revelations of fake news, foreign manipulation and monopolistic abuses. As I sat with him in a sweltering room in Gaza, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was preparing to defend his creation in the European Parliament, while the optimism of social media fostering Arab Spring revolts felt like another age. Yet in Palestine, despite just four hours of electricity a day on average, online forums buzz with lively debate and discussion from domestic and diaspora users under the nose of Hamas.

There are many more examples of how technology is being used to challenge despotism and undermine censorship, not just through social media and secure communications. In Turkey activists uploaded Wikipedia after it was banned by using a decentralised network called InterPlanetary File System that cannot be blocked since data is stored in multiple places. Bitcoin was adopted widely in Venezuela, after the Maduro regime wrecked the country’s currency and unleashed hyper–inflation; in Afghanistan, it has been used to pay women whose husbands and families bar them from having bank accounts, offering them some financial autonomy. Even in North Korea, glimpses of the outside world filter through the bamboo curtain thanks to exiles smuggling in data sticks packed with information on human rights, South Korean soap operas and Hollywood films.

At the same time, autocratic regimes are turning to technology to tighten their grip, most notably China with its horrific social credit plan that aims to constantly monitor everyone through their online transactions and movements, rewarding compliant behaviour while penalising those showing signs of dissent. Yet experts believe even this dark concept can be defeated by digital advances. “New decentralized technologies are being born today that offer censorship–resistance and ownership of data and value which will empower activists in the same way that encrypted communications have done,” said Alex Gladstein of the Human Rights Foundation.

Next week in Oslo his organisation holds its annual Freedom Forum, nicknamed “Davos for Dissidents”, at which there is a day–long session exploring these issues. Gladstein believes the geeks can stay one step ahead of even the worst dictatorships. “The future is one where activists and journalists will be able to interact and build networks in ways that governments find very hard to stop.” We must hope he is right – and that for all its faults, technology can still prove a boon to boost democracy around the planet rather than the corrosive force it seems so often.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe